This blog post presents our recent IJHCS paper Conversational agents for fostering curiosity-driven learning in children.

Curiosity : a key factor for enhancing learning experiences and outcomes

Curiosity is defined as “a desire to know, see or experience that motivates exploratory behavior oriented towards the acquisition of new information” [2]. It is an important factor that can improve children’s ability to take charge of complex activities [3], to engage in learning [4], or to memorize new information better [5]. Indeed, our brain learns and memorizes the information better when we seek it and find it on our own, by asking questions or exploring the environment for example, and not by passively receiving it [6]. Given its importance for learning, several recent studies have focused on the study of curiosity in the classrooms, with the goal of designing pedagogical interventions that can foster this ability in young children. Their obseravtions showed that it is, indeed, a malleable skill [7] that can be elicited by verbal and nonverbal cues [8,9,10], by promoting comfort with uncertainty and encouraging questioning and exploration to resolve it. However, and despite different efforts, recent reports show that today’s educational content does very little to encourage children to be curious, generally reducing them to one correct answer and not allowing them enough space to ask questions and explore, the main expressions of epistemic curiosity.

Curiosity during learning : the major brakes

Questioning behaviors, which are the primary expressions of epistemic curiosity in children, are almost absent in today’s classrooms. Several factors may be responsible for this; in particular, the so-called “knowledge illusion”: children’s tendency to overestimate their knowledge levels and not be aware of the information they might be missing - this is the notion of “knowledge gaps” [16]. This problem stems mainly from their lack of reflection on their own learning and their inability to assess their own knowledge levels.

This capacity of self-assessment and the awareness of knowledge gaps are very important factors to stimulate the curiosity of the individual. Indeed, when we realize that we do not have a piece of information or that our knowledge does not correspond to the one necessary to understand the environment, a knowledge objective to acquire will appear. This objective is usually a motivator for a curiosity-driven behavior -such as generating a question-, which is initiated in order to compensate for the identified “knowledge gap” and acquire the missing knowledge [17]. Other factors that may prevent children from asking questions in class are their inability to formulate syntactically correct questions [11], or their fear of judgments from peers or their teachers [12].

To remedy these problems, several research studies encourage teachers to set up specific training sessions to familiarize children with the notions of self-evaluation and questioning and to help them feel more comfortable with their uncertainties. However, such workshops can be difficult to create as they require teachers to find specific teaching materials for each knowledge component and activity, which can be a particularly time-consuming task [1,10].

The “Kids Ask” project

In this context, and in order to support teachers in this task, our “Kids Ask” project leverages new technologies and proposes a curiosity training based on the awareness of “knowledge gaps”; paying particular attention to self-assessment and how to avoid the “knowledge illusion” trap. In particular, we implement conversational agents capable of stimulating questioning and exploration motivated by the desire to compensate for specific missing information. Our work is notably motivated by the positive effects that this type of technologies has shown on children’s learning strategies, their divergent thinking, as well as for the construction of good social relationships with them [13].

Design

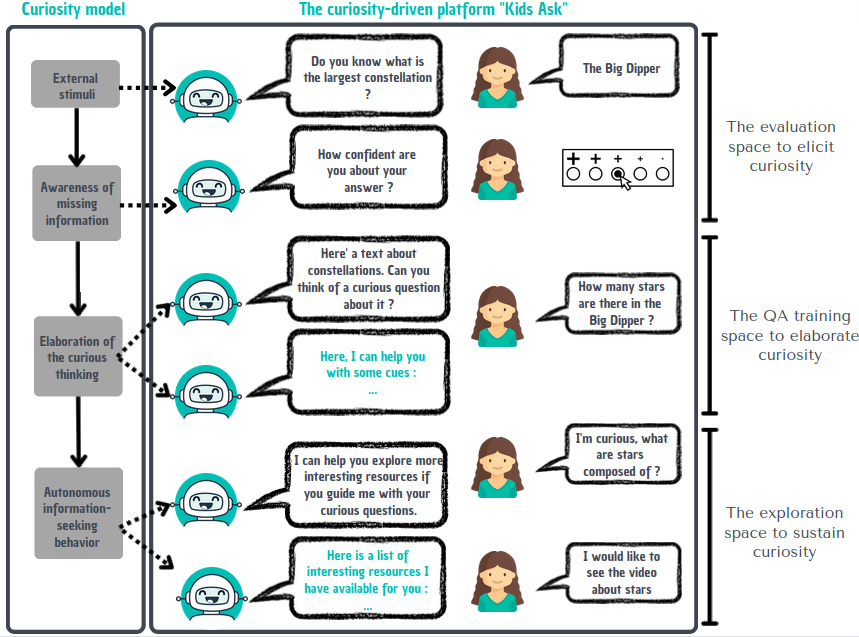

“Kids Ask is an web-based educational platform prototype, that involves interaction with a conversational agent. The platform is designed to help children identify their uncertainties, or “knowledge gaps”, generate questions to compensate for these gaps and, finally, use their questioning skills to explore and acquire new knowledge autonomously by following their curiosity.

To meet this objective, “kids Ask” offers three work spaces:

- Curiosity stimulation Space: The agents in this space offer quizzes on different topics and try to make students aware of gaps in their knowledge by encouraging them to report confidence levels in the answers they give. We use this strategy to probe students’ meta-cognition and attempt to arouse their curiosity by making them aware of gaps in their knowledge. Indeed, these strategies allow children to think more deeply about what they know and do not know and thus be able to defer more uncertainties [14]-the first step to adopting curious behaviors.

- Curiosity elaboration space: In a second step, our agents aim to help children go one step further than the identification of uncertainty: we want to train them to know how to express these uncertainties and to be able to pursue them by asking the appropriate questions.

To do this, the agents propose reading-comprehension tasks and specific cues for formulating questions that are said to be “divergent” from the texts. These are questions that bring up new information about the text and ask students to make hypotheses, connections between different ideas, etc. The agents help the students in this exercise by proposing precise linguistic and semantic clues that lead to this divergent thinking. The idea here is to propose “knowledge gaps” to the students and to encourage them to pursue them by formulating high-level questions. By doing this exercise, children could thus acquire new information that they would have looked for on their own, and which is important for a better understanding of the text. We choose to focus on training divergent questioning because it is an ability that induces more curious thinking and involves the use of more cognitive processes [15]. - Curiosity maintenance space: In order to help children stay in curious states, our agents encourage them to mobilize their questioning abilities to explore educational resources available in the platform and perform autonomous, organized, and personalized investigations. The purpose of this space is to train children to take time to evaluate the new information they acquire and ask themselves if they are satisfied with it or if it raises new questions in them. Such exercises help avoid the trap of the “illusion of knowledge” and the “premature” interruption of learning cycles.

Figure 1. Illustration of the 'Kids Ask' platform features, with relation to our curiosity model

Figure 1. Illustration of the 'Kids Ask' platform features, with relation to our curiosity model

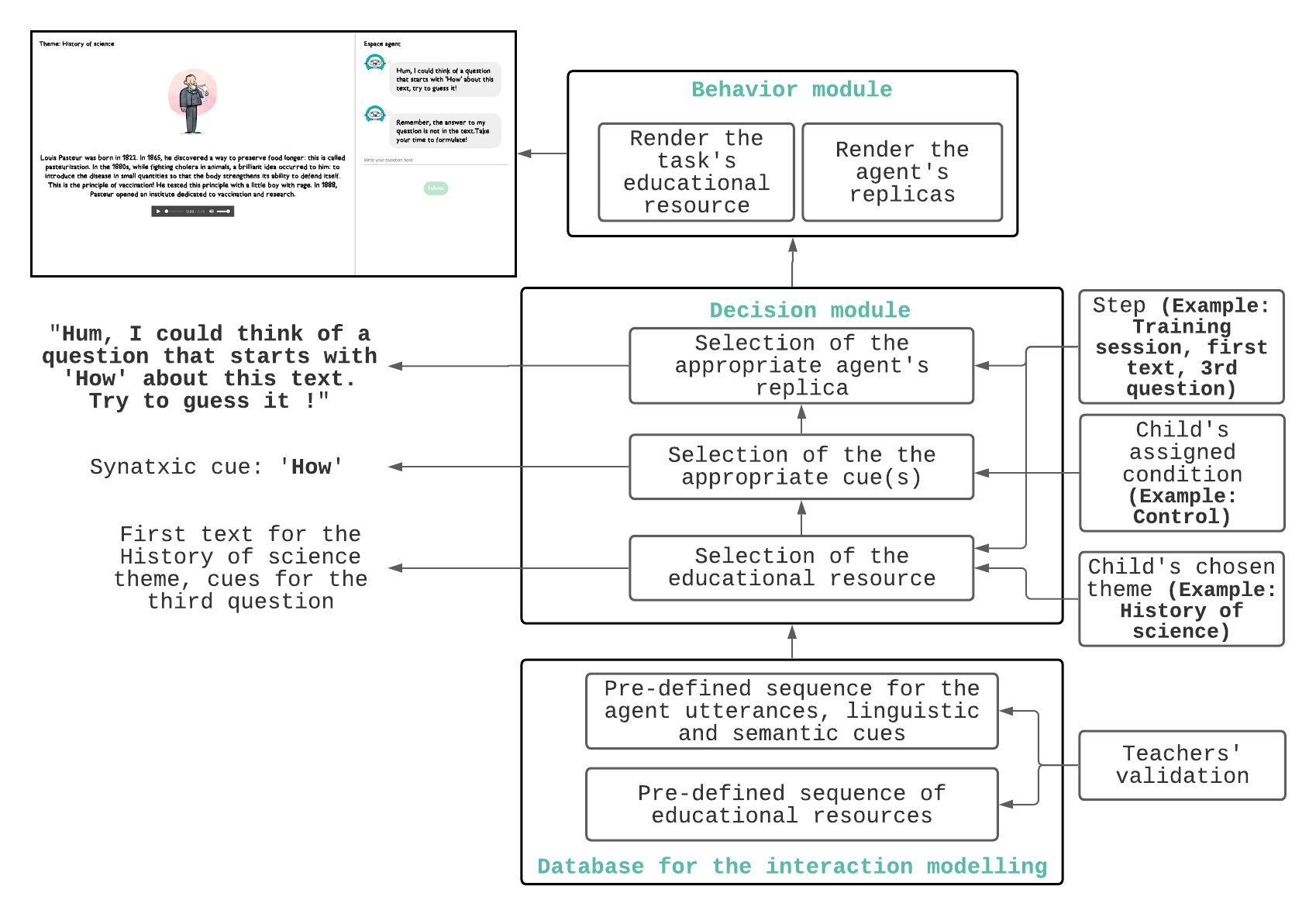

Technical implementation

The interface was programmed in JavaScript using the REACT library and was connected to a RESTful API to publish and retrieve the interaction data. The behavior of the agent in terms of selection of the adequate cue(s) to offer was predefined and hand-scripted: it was connected to a database containing the different text resources and every text had a sequence of linguistic and semantic cues linked to it. Depending on the child’s condition, the agent’s automaton composes the dialogue utterances in order to include the appropriate support. We changed the utterances between the questions to avoid repetition in the agent’s dialogue: a replica is not executed if it has been delivered during the previous question.

Our current implementation had no natural language processing methods to condition the agent’s behavior: the recommendation system in the exploration space was only based on an automaton that shows the resources related to the topic of choice of the child. Also, the type of question entered by the child was only assessed later on during the data analysis phase.

Figure 2. System design

Figure 2. System design

Testing with children

The “Kids Ask” platform was tested with four classes from two different French elementry schools; participants were aged between 9 and 10. In order to investigate the efficiency of our approach (described above), we implemented two different versions of “Kids Ask” :

- An experimental version : where participants interacted with “incentive” agents, i.e., agents that propose “knowledge gaps”

- A control version : where participants interacted with “neutral” agents, i.e., agents that only ask if the child has a question about the text without giving any hints or cues.

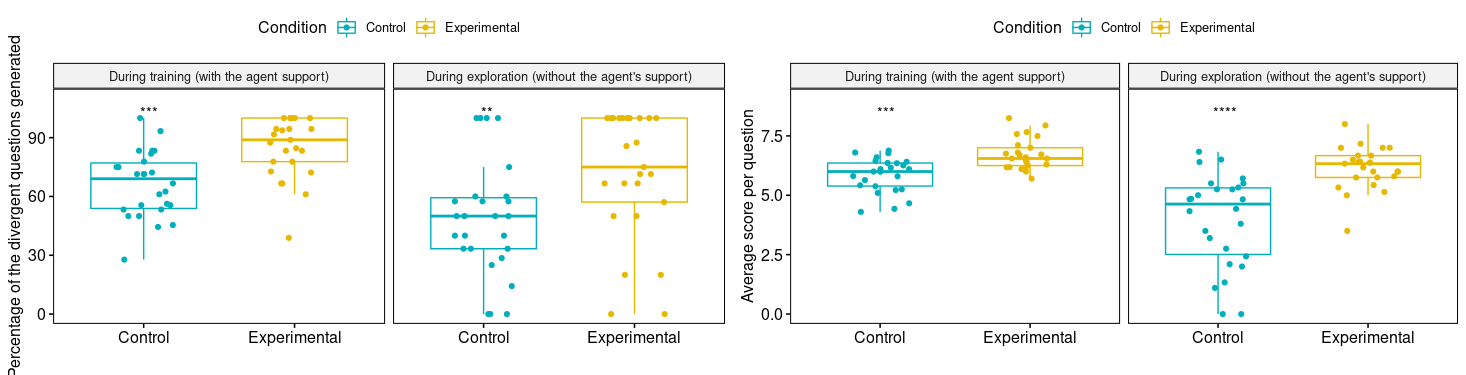

- Children’s ability to ask correct curiosity-based questions during the training: The results of the interaction showed that children that had the experimental version of “Kids Ask” (i.e., the incentive agents) asked significantly more divergent questions during their training than those who had the “neutral” agents. Questions were also of higher syntactic quality for participants who had the help of the incentive agents.

Figure 3. (A) Children's ability to ask curiosity-driven questions (i.e., higher-level divergent questions) is significantly better when having the support of the incentive agents (B) Children's ability to ask correct questions syntax-wise is significantly better when having the support of the incentive agents.

Figure 3. (A) Children's ability to ask curiosity-driven questions (i.e., higher-level divergent questions) is significantly better when having the support of the incentive agents (B) Children's ability to ask correct questions syntax-wise is significantly better when having the support of the incentive agents.

-

Children’s ability to use curious question-asking to lead autonomous explorations of the pedagogical resources available: Our results showed that the incentive agents were more effective in helping children maintain autonomous explorations of the educational resources. We also showed that the exploration length was in line with children’s ability to generate the relevant curious questions. However, our results were not conclusive as to the patterns of explorations of these resources. Indeed, we saw similar entropies in the transitions between the resources that children from the two groups adopted during their information-searching cycles.

-

Children’s acheived domain-knwoledge learning progress: Finally, our results also showed a strong and positive relationship between the intensity of children’s curiosity-driven behaviors and their ability to acheive domain-knowledge learning progress.

Together, our results suggest that the more our agents are able to help children become aware of their knowledge gaps, the better they can maintain their curiosity-driven information-seeking behaviors and the more likely they are to acquire new knowledge independently.

Conclusion and future directions

With this project, we show that curiosity-driven behaviors such as curiosity-driven questioning and independent explorations can be trained on and enhanced with the help of educational technologies in general and conversational agents more particularily. We also show that these behaviors have a direct positive impact on the learning progress children can make. For future directions, we aim to work on the automation of our agents’ curiosity-prompting behaviors in order to facilitate their implementaion on larger scale and in different school activities. For this, we are studying the possibility to leverage the advances in the natural language processing field in order . Our work and results motivate the implementation of such approaches in both classrooms and online learning environments.

Cite this blog post

@misc{,

TITLE = ,

AUTHOR = {Abdelghani, Rania and Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves and Law, Edith and de Vulipillieres, Catherine and Sauzeon, Helene},

YEAR = {2022},

HAL_ID = {hal-03810322},

HAL_VERSION = {1},

}

Cite our IJCHS 2022 paper

@article{ABDELGHANI2022102887,

title = {Conversational agents for fostering curiosity-driven learning in children},

journal = {International Journal of Human-Computer Studies},

volume = {167},

pages = {102887},

year = {2022},

issn = {1071-5819},

doi = {https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2022.102887},

url = {https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1071581922001112},

author = {Rania Abdelghani and Pierre-Yves Oudeyer and Edith Law and Catherine {de Vulpillières} and Hélène Sauzéon},

keywords = {Human–computer interface, Cooperative/collaborative learning, Teaching/learning strategies, Improving classroom teaching}

}