This blog post presents our recent ICLR paper Learning to Guide and to Be Guided in the Architect-Builder problem. The codebase accompanying this paper is available in the following repo. A recording of the paper presentation is also available on YouTube.

Humans are incredibly good at teaching and learning from each other. And impressively, they are able to do so in contexts where they share little to no common ground – such as a shared language or a known collective objective. In early stages of their development, children can interpret social cues from their parents to detect their intention and interact with them. In the following picture for instance, a preverbal infant that did not yet learn to produce words can learn to stack objects by reacting to guidance provided by a caregiver. In these types of interactions, not only does the child discover a new task, she also learns to interact and communicate with others.

A picture of a child learning to stack cubes from interactions with a caregiver (image taken from here)

A picture of a child learning to stack cubes from interactions with a caregiver (image taken from here)

It turns out that social interactions are central to child development [1]. Long before they learn about language, children constantly adapt to the social context in which they evolve. For instance, they demonstrate ‘social sensitivity’ adapting their behavior to emotions [2] (see this video). They also detect pedagogical signals and are able to infer the communicative intention of a caregiver [3] (see this recent paper [4] section I.A for a thorough list of children learning properties)

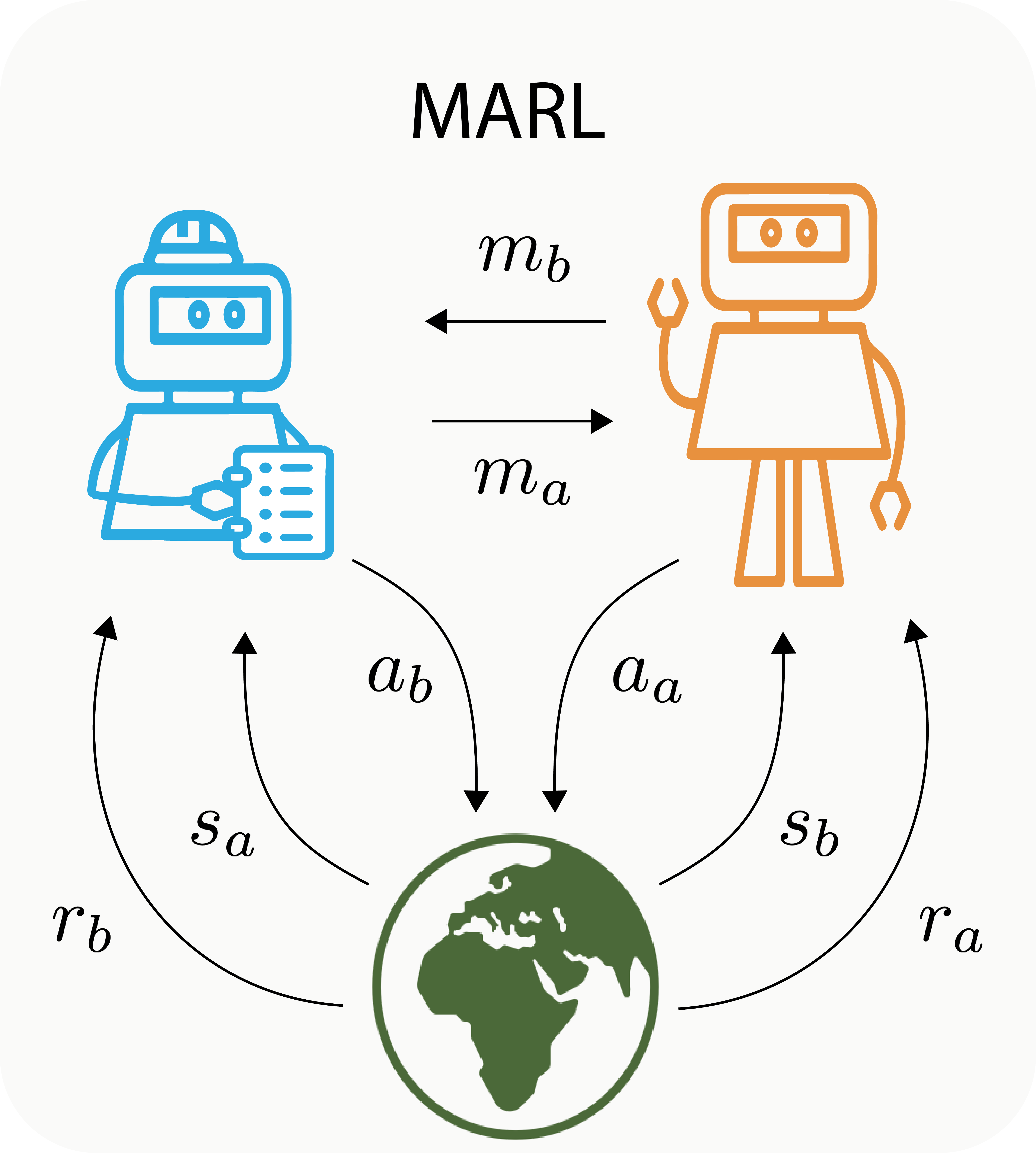

Therefore it seems that pre-verbal communication enables children to acquire new skills in absence of direct reinforcement signals, demonstrations or even a shared communication protocol. In the quest to design interactive artificial agents, such flexible learning skills look like a desirable feature. But how do we make progress in this direction? How can artificial agents figure out what to do and learn relevant behaviors without any common ground? On the one hand, HRI focuses on human teaching robots and investigates how a robot-learner can figure out what a human-teacher wants it to do [5] [6]. On the other hand, Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning (MARL) [7] can model robot-robot interactions by placing multiple agents in an environment and training them to solve collaborative tasks. Yet, in MARL, all agents have access to a reward signal defined by the collaborative task they need to achieve. This assumption is not really representative of a child interacting with a caregiver since the reward is an external signal shared between agents. The question is then how can we come up with a realistic setting where two agents that share no common ground can learn a communication protocol to solve a task?

We propose to answer this question by drawing inspiration from Experimental Semiotics [8]. Experimental Semiotics is a discipline that aims at investigating, in the laboratory, how humans develop common grounds in order to collaborate. It uses experiments to model the development and the emergence of communication protocols. However, interactions between humans are complex and involve many dimensions (symbols, eye gaze, gesture, posture). To get a fine grasp of the underlying mechanisms at hand, experimenters try to study these dimensions in isolation.

In this blog post, we will review a recent experiment studying the emergence of communication between humans in a co-construction task involving lego blocks. We will then present the Architect-Builder Problem (ABP), a framework that draws inspiration from this experiment to propose a new interactive learning paradigm for artificial agents. We will then discuss potential real world applications of the ABP before moving on to the study of Architect-Builder Iterated Guiding (ABIG), a solution to the ABP.

The Co-Construction Game

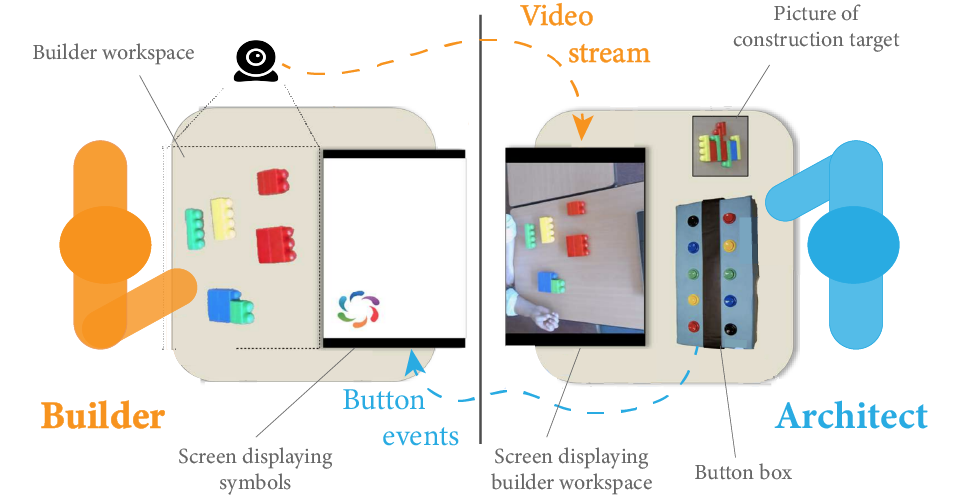

The Co-Construction game is an experiment proposed by Vollmer et al. [9]. It aims at studying how humans can align and create common ground to solve a collaborative task. The game involves two players: an Architect and a Builder, each having a separate role. Their goal is to build a lego construction. Agents are located in separate rooms. The Architect has a picture of the construction target but cannot manipulate the blocks. In the other room, the builder can move the blocks around but does not know what it needs to build. The two agents can interact via a constrained communication channel. The architect can press buttons in order to display abstract symbols on the screen of the builder’s room. The architect can also see the builders’ workspace thanks to a video stream.

Communication is made challenging because agents only interact with abstract symbols that have no a priori meanings. In order to succeed, a pair must progressively establish a communication convention – or protocol – through the interplay and history of their mutual interactions. The builder needs to simultaneously learn the task and the meaning of messages while the architect has to adapt to the builder’s reactions.

This game is often deemed impossible or extremely hard by the participants. What about you? Would you expect to succeed? It seems pretty hard to associate meanings to messages on the fly while performing a task. To demonstrate this concept, Jonathan Grizou developed this online game where you need to crack the code of a vault by learning the meaning of the interface buttons. In the Co-Construction game, it turns out that the subjects did succeed but it took time for them to agree on a protocol (approximately 20 minutes). The solution they agree upon is not so advanced. Successful dyads always converge to a positive/negative type of protocol similar to the Hot and Cold game we used to play as children. An example of an interaction in a face to face scenario is given in the following video (note that the participants are instructed to remain impassive and only communicate with the provided tools).

In a recent ICLR paper [10], we investigate if such behaviors can be observed between artificial agents. For this purpose we translated the Co-Construction game into a sequential decision making formalism that we coined the Architect-Builder Problem.

The Architect-Builder Problem

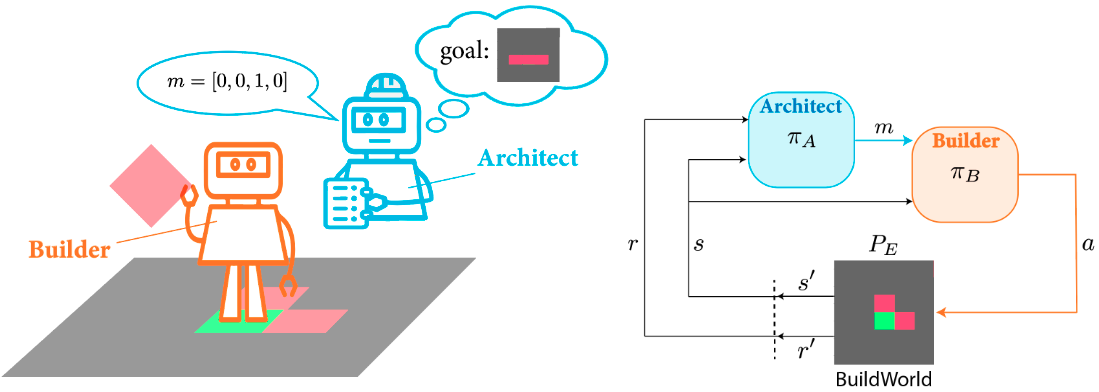

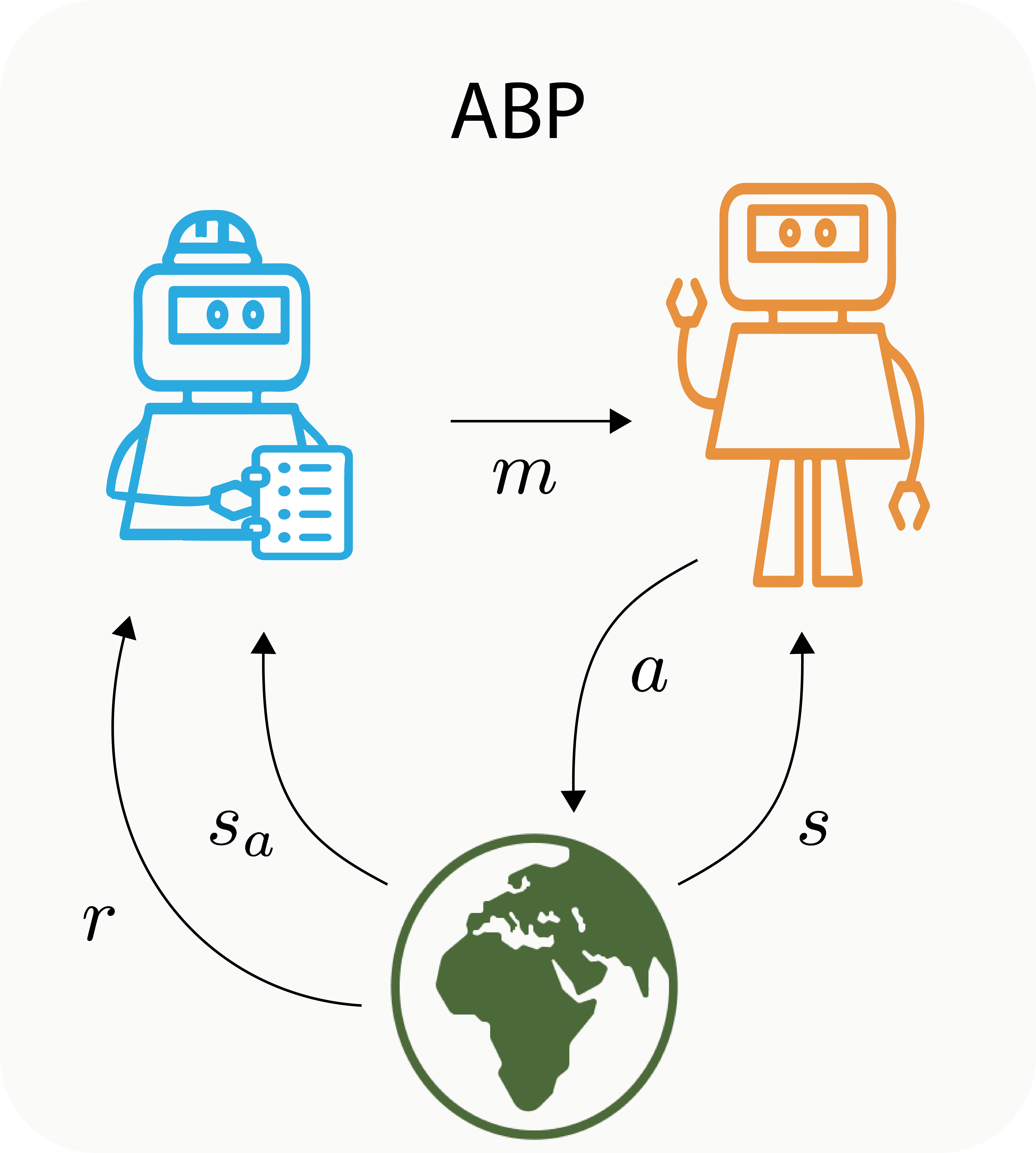

To stick with the spirit of the Co-Construction game, we designed a simple construction environment called BuildWorld. BuildWorld is a 2D grid world in which the builder can navigate and manipulate blocks to construct various shapes. In the ABP, the two agents have asymmetrical roles. Only the architect knows about the target construction (the goal). In a Markov Decision Process, this means that only the architect perceives the rewards given by the environment. However, the architect cannot make any actions in the environment. It can only observe the states ($s$) of the environment. The interactions unfold in the following sequence. First, the architect produces a message ($m$) given a certain state and a goal. The builder then receives the message and takes an action ($a$) that makes the environment transition to a new state ($s’$).

Sketch of the Architect-Builder Problem and sequential diagram of interactions.

Sketch of the Architect-Builder Problem and sequential diagram of interactions.

In this new multi-agent interactive learning setting where only one agent perceives the reward, we make the assumption that the Architect has access to the environmental reward $r$ and transition functions $P_E$. In less formal terms, this means that the Architect knows about the dynamics that govern the manipulations of blocks. We believe that this assumption is sound and matches with the conditions in which the Co-Construction game is performed where human architects know how to stack blocks in desired configuration even if they cannot physically do it themselves.

At this point of the post you might say: OK the ABP is a faithful implementation of the Co-Construction game but why does it make it an interesting learning setup for artificial agents? There are several reasons for that.

First it is interesting because it is a new way to approach multi-agent learning. Most of recent research [7] study multiple agents that have the same learning mechanism to learn to solve a collaborative task. Crucially, in such a setup, all the agents perceive the reward associated with the task and act to influence the environment transitions. In our case, we consider agents with different learning mechanisms where one totally ignores the task to perform while the other is aware of the task but cannot directly drive the environment towards its completion. We believe that these constraints make the ABP a challenging and realistic setup to study the emergence of communication.

We like to think that the ABP is not only designed to study the emergence of communication for collaboration. It is also a relevant test bed to foster fundamental research around the mechanisms underlying interactive teaching and interactive learning. In fact, the recent IGLU NeurIPS Competition proposed to investigate these questions in a setup similar to ours with an Architect and a Builder interacting with natural language in a 3D-rendered construction environment.

ABP is interesting because it has the potential to model real world applications. Indeed, it shares similar assumptions with Brain Computer Interfaces (BCI). A typical example of a BCI is a robotic arm controlled by brain signals.

An example of a BCI (image taken from here).

An example of a BCI (image taken from here).

With such systems, it is impossible to anticipate the intentions of users and the tasks that they will try to perform. Thus, we cannot devise a reward signal that would help the computer and the brain agree on a communication code. A solution to this problem is to calibrate the machine. This is often done by using supervised learning to map brain signals to a computer interpretable code that is later used during interaction. However, this calibration phase is time consuming and depends on the user and the task. On top of that, the initial placement of sensors that read user signals may move over time requiring re-calibration. Recent research proposes to tackle this problem via Interaction-Grounded Learning [11], where “the learner must deduce a grounding for the feedback solely via interaction” just as the builder needs to learn to solve the task solely through the messages it receives by the architect in the ABP. This can enable online-calibration of BCIs [12] where (1) only the human (the brain) knows what she wants to do ; (2) only the robotic arm can act in the environment and (3) the mapping from brain signals to arms movement is not know a apriori but must emerge from the interactions between the human and the BCI.

Finally, the Architect-Builder Problem should be differentiated from Hierarchical Reinforcement Learning (HRL). In ABP the builder does not have access to any reward while in HRL the builder receives a reward given by the architect. So HRL assumes that there is a “reward channel” through which the architect can explicitly set the learning signal of the builder. In the case of a Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) where a user must control a prosthetic arm using only brain signals, HRL would require us to assume that the user is directly communicating a reward signal to the robotic arm. In other it would rely on a way to translate brain signals into scalar values indicating how much the user is satisfied with what the arm is doing. This is precisely the non-trivial calibration problem that BCIs are trying to address. Another way of looking at it is to note that the HRL setting requires to pre-define the communication protocol between the agents (i.e. “messages are scalars that must be interpreted as a reward and maximized by the builder”) and does not have agents negotiate and invent one.

Architect-Builder Iterated Guiding (ABIG)

We have seen that learning a task from interaction without reward is an interesting problem in different scientific fields including experimental semiotics and AI, as well as applications such as BCI. Let’s now go over our proposed solution to efficiently solve this problem.

The ABP contains two main challenges:

- Non stationarity: Because both the architect and the builder are learning at the same time. Their respective learning environments include the learning dynamics of each other.

- No reward: The Builder never perceives a reward. It has no learning signal so how can the Builder learn?!

To address these two challenges we rely on two priors:

- To recover stationarity, we break down learning into Interaction Frames (or Pragmatic Frames) [13] during which each agent learns sequentially in turn. Pragmatic Frames provide a learning environment for children during which information is structured in recurrent and sequential interactions. It has been shown that it facilitates the emergence of language [14].

- To find a learning signal for the Builder we use the Shared Intent prior. We assume that both the Architect and the Builder aim at maximizing the same objective (solving the task at hand).

Using these two priors we introduce the Architect-Builder Iterated Guiding algorithm. ABIG is an iterative method that alternates between a Modeling and a Guiding frame.

Diagram of the ABIG algorithm.

Diagram of the ABIG algorithm.

During the first frame (the modeling frame) the Builder is fixed and the Architect sends random messages to observe the Builder’s reaction. Doing so, it constructs a dataset $(s,m,a,s’)_t$ and learns a model of the builder $\tilde{\pi}_B$ using Behavioral Cloning (BC)

In the second frame (the guiding one) the architect uses the model of the builder alongside with the reward signal to plan and pick the messages that will maximize the reward. In other words, it will select messages that would yield actions by the builder that would generate high rewards. Once the architect has produced a message, the builder receives it and picks an action according to its policy $\pi_B$. During these interactions the builder stores the guiding data $(s,m,a,s’)_t$ and this is when the shared intent prior comes into play. If the builder assumes that the guiding trajectory generated by the architect maximizes the reward, this means that the guiding trajectory that it just stored are in fact demonstrations of how to solve the task. Therefore the builder can use Self-Imitation (doing BC on the guiding trajectory) to improve its policy.

By iterating between these two frames, we show in our paper that Architect-Builder pairs can learn successful communication protocols that not only allow them to solve construction tasks but that can also solve new tasks in zero-shot transfer. Below are rollouts of interactions leveraging a protocol (learned by placing a block at a given location) to construct multiblock structures with shapes “Y” and “O”. Interestingly, throughout learning, agents converge to very simple protocols where the builder’s actions are led by messages rather than states (the mutual information between states and actions decreases while the one between messages and actions increases), meaning that the architect is suggesting actions to the builder.

Example of interactions using successful protocols learned with ABIG.

Example of interactions using successful protocols learned with ABIG.

Conclusion

In this work we propose a versatile new learning paradigm well suited to study for example the constrained emergence of communication or the calibration of Brain-Computer Interfaces. It is exciting to realize all the possible avenues towards which this setting could be extended: more complex tasks, varied communication channel and recurrent policies for more complex communication protocols; relaxing the sequentiality between modeling and guiding frames to allow for online and continual learning, having the builder internalize the solved task so that it can be autonomous and not rely on architect’s messages anymore, etc.

More fundamentally, ABP is a first try toward shifting the learning paradigm from specified conventions/interfaces and rewards as learning signals to more flexible and negotiable social supervisions. This resembles how we humans co-adapt to using many gestures in a personalized way when working with each other.

Cite this work

@inproceedings{

barde2022learning,

title={Learning to Guide and to be Guided in the Architect-Builder Problem},

author={Paul Barde and Tristan Karch and Derek Nowrouzezahrai and Cl{\'e}ment Moulin-Frier and Christopher Pal and Pierre-Yves Oudeyer},

booktitle={International Conference on Learning Representations},

year={2022},

url={https://openreview.net/forum?id=swiyAeGzFhQ}

}

- L. S. Vygotsky. Thought and Language 1934.

- T. M. Field, R. Woodson, D. Cohen, R. Greenberg, R. Garcia, K. Collins. Discrimination and Imitation of Facial Expressions by Term and Preterm. Infant Behavior and Development, 6(4), 485-489. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(83)90316-8.

- G. Csibra, G. Gergely. Natural Pedagogy. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009 Apr;13(4):148-53. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.005. Epub 2009 Mar 13. PMID: 19285912.

- O. Sigaud, A. Akakzia, H. Caselles-Dupré, C. Colas, P.Y. Oudeyer, M. Chetouani. Towards Teachable Autotelic Agents. 2021.

- T. Cederborg. Artificial Learners Adopting Normative Conventions From Human Teachers. Journal of Behavioral Robotics 2017.

- J. Grizou, M. Lopes, P.-Y. Oudeyer. Robot learning simultaneously a task and how to interpret human. ICDL 2013.

- R. Lowe, Y. Wu, A. Tamar, J. Harb, P. Abbeel, I. Mordatch. Multi-Agent Actor-Critic for Mixed Cooperative-Competitive Environments. NeurIPS 2017.

- B. Galantucci and S. Garrod. Experiment Semiotics: a Review. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2011.

- A.-L. Vollmer, J. Grizou, M. Lopes, K. Rohlfing, P.-Y. Oudeyer Studying the Co-Construction of Interaction Protocols in Collaborative Tasks with Humans. ICDL 2014.

- P. Barde, T. Karch, D. Nowrouzezahrai, C. Moulin-Frier, C. Pal, P.-Y. Oudeyer. Learning to Guide and to Be Guided in the Architect-Builder Problem. ICLR 2022.

- T. Xie, J. Langford, P. Mineiro, I. Mommennejad. Interaction-Grounded Learning. ICML 2021.

- J. Grizou, I. Iturrate, L. Montesano, P.-Y. Oudeyer, M. Lopes. Calibration-Free BCI Based Control. Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, AAAI'14.

- A.-L. Vollmer, B. Wrede, K. J Rohlfing, P.-Y. Oudeyer. Pragmatic frames for teaching and learning in human–robot interaction: Review and challenges. Frontiers in neurorobotics, 10:10, 2016.

- J. Bruner. Child’s talk: Learning to use language. Child Language Teaching and Therapy 1(1):111–114, 1985.

The Co-Construction game specifications: link to

The Co-Construction game specifications: link to