|

|

|

|

Deep Reinforcement Learning algorithms have attracted unprecedented attention due to remarkable successes in games like ATARI and Go, and have been extended to control domains involving continuous actions. However, standard deep reinforcement learning algorithms using continuous actions like DDPG suffer from inefficient exploration when facing sparse or deceptive reward problems.

One natural approach is to rely on imitation learning, i.e. leveraging observations of a human solving the problem. However, humans cannot always help. They can be unavailable, or simply unable to demonstrate a good behavior (e.g. how to demonstrate locomotion to a 6-leg robot).

Another approach relies on the use of various forms of curiosity-driven Deep RL. This generally consists in adding an exploration bonus term to the reward function, measuring quantities such as information gain, entropy, uncertainty or prediction errors (e.g. [Bellemare et al.]) . Sometimes the reward function is even ignored and replaced by such an intrinsic reward [Pathak et al., 2017]). However, it is challenging to leverage them in environments with complex continuous action spaces, especially on real world robots.

In our recent ICML 2018 paper, we propose to leverage evolutionary and developmental curiosity-driven exploration methods that were initially designed from a very different perspective. These are population-based approaches like Novelty Search, Quality-Diversity or Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes. The primary purpose of these methods has been to enable autonomous machines to discover diverse repertoire of skills, i.e. to learn a population of policies that produce maximally diverse behavioral outcomes. Such discoveries have often been used to build good internal world models in a sample efficient manner, e.g. through curiosity-driven goal exploration [Baranes and Oudeyer, 2013]. This led to a variety of applications where real world robots where capable to learn very fast complex skills [Forestier et al.,2017] or to adapt to damages [Cully et al., 2015].

Our new paper shows that the strengths of monolithic Deep RL methods and population-based diversity search methods can be combined for solving RL problems with rare or deceptive rewards. The general idea is as follows. In the exploration phase, we use a population-based diversity search approach (in the experiments below, a simple form of Goal Exploration Process [Forestier et al, 2017]). During this phase, diverse goals are sampled, leading to sampling corresponding small-size neural network policies, which behavioral trajectories are recorded in an archive. While the sampling process is not influenced at all by the extrinsic reward of the RL problem, these rewards are nevertheless observed and memorized. Then, in a second phase, all trajectories (and associated rewards) discovered during the first phase are used to initialize the replay buffer of a Deep RL algorithm.

The general intuition is that population-based pure diversity search enables to find rare rewards faster than Deep RL algorithms, or to collect observation data that is very useful to Deep RL algorithms for getting out of deceptive local minima. However, as Deep RL algorithms are very strong at exploiting reward gradient information when it is available, they can be used to learn policies that refine those found during the diversity search phase.

Our experiments use a simple goal exploration process for the first phase, and several variants of DDPG for the second phase.

We show that, and analyze why:

- DDPG fails on a simple low dimensional deceptive reward problem called Continuous Mountain Car,

- GEP-PG obtains state-of-the-art performance on the larger Half-Cheetah benchmark, reaching faster and higher performances than DDPG alone,

- The diversity of outcomes discovered during the first phase correlates with the efficiency of DDPG in the second phase.

The methodology

Our experiments follow the methodological guidelines presented in [Henderson et al, 2017]:

- we use standard baseline implementations and hyperparameters of DDPG,

- we run robust statistical analysis, averaging our results over 20 different seeds for each algorithm,

- we provide the code of the algorithm, and the code to make the figures, here.

The environments

Continuous Mountain Car (CMC) is a simple 2D problem available in the OpenAI Gym environments. In this problem, an underpowered car must learn to swing in a valley in order to reach the top of a hill. Success yields a large positive reward (+100) while there is a small penalty for the car energy expenses \((-0.1 \times \mid a\mid^2)\).

In Half-Cheetah (HC), a 2D biped must learn how to run as fast as possible. It receives observations about its absolute and joints positions and velocities (17D) and can control the torques of all joints (6D).

Continuous Mountain Car

|

Half Cheetah

|

The GEP-PG approach

GEP-PG, for Goal Exploration Process - Policy Gradient, is a general framework which sequentially combines an algorithm from the Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Process family (IMGEP) [Forestier et al, 2017] and Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG) [Lillicrap, 2015].

DDPG

DDPG is an actor-critic off-policy method which stores samples in a replay buffer to perform policy gradient descent (see original paper [Lillicrap, 2015] for detailed explanations of this algorithm). In this paper, we use two variants:

- DDPG with action perturbations, for which an Ornstein-Uhlenbeck noise process is added to the actions.

- DDPG with parameter perturbations, where an adaptive noise is added directly to the actor’s parameters, see [Plappert, 2018] for details.

GEP

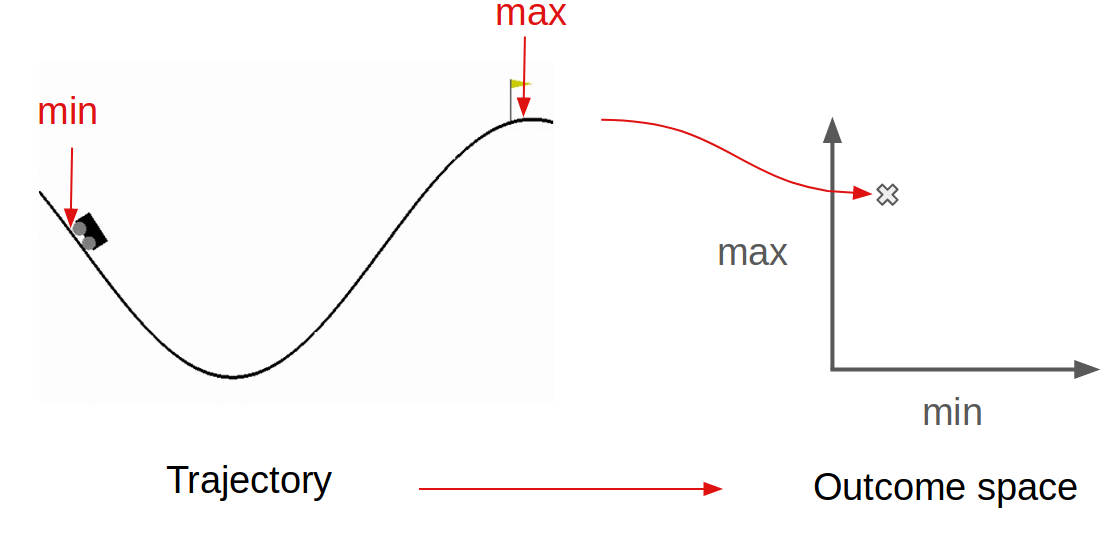

Here, we use a very simple form of goal exploration process. First, we consider neural network policies, typically smaller in size than the one learnt in the PG phase. Second, we define a “behavioral representation” or “outcome space” that describes properties of the agent trajectory over the course of an episode (also called “roll-out” of a policy). For CMC, the minimum and maximum position on the x-axis could be used as behavioral features to define the outcome space:

Every time a roll-out is made with a policy, the policy parameters and the corresponding outcome vector are stored inside an archive. In addition, one stores the full (state, action) trajectory and the extrinsic reward observations: these observations are used in the second phase, but they are not used in the data collection achieved by the goal exploration process.

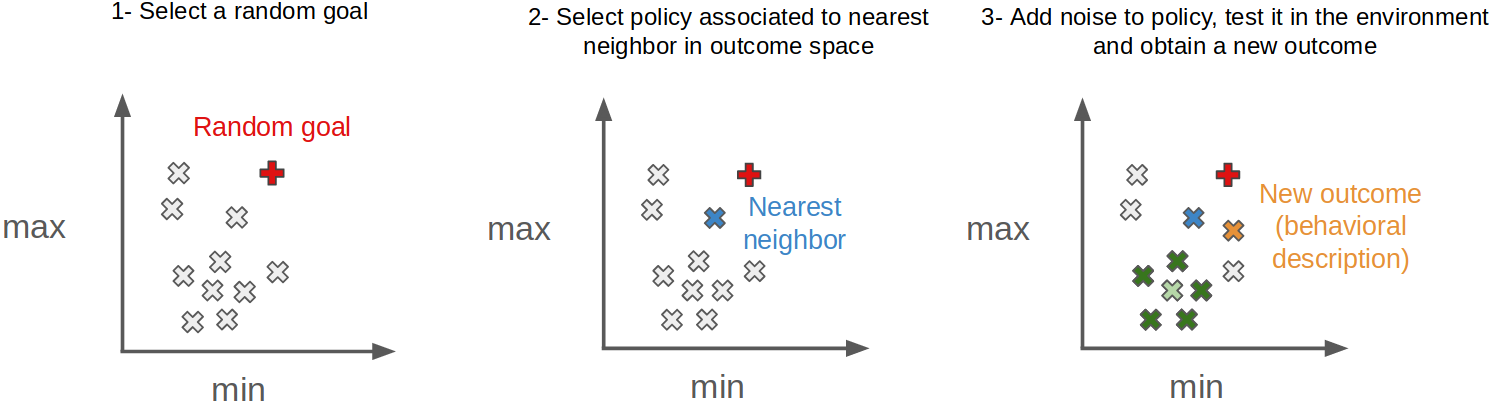

The GEP algorithm then repeats the following steps (Figure below):

- sample a goal at random in the outcome space,

- find the nearest neighbor in outcome space archive and select the associated policy,

- add Gaussian noise to policy and play it in the environment to obtain a new outcome,

- save the new (policy, outcome) pair in the archive.

Other implementations of goal exploration processes perform curiosity-driven goal sampling (e.g. maximizing competence progress) in step 1, or use regression-based forward and inverse models in step 2. However, the very simple form of goal exploration used here was previously shown to be already very efficient to discover a diversity of outcomes. This may seem surprising at first as it does not include any explicit measure of behavioral novelty. Yet, when one samples a random goal, there is a high probably that this corresponds to a vector in outcome space that is outside the cloud of outcome vectors already produced. As a consequence, when looking at the nearest-neighbor, there is a high probability to select a an outcome that is on the edge of what has been discovered so far. And thus trying a stochastic variation of the corresponding policy tends to push this edge further, thus discovering novel behaviors. So, this simple GEP implementation behaves similarly to the Novelty-Search algorithm [Lehman & Stanley, 2011], yet never measuring explicitly novelty.

Besides, one can note that GEP maintains a population of solutions by storing each (policy, outcome) pair in memory. This prevents catastrophic forgetting and enables one-shot learning of novel outcomes. The policies associated to these behaviors can easily be retrieved from memory by using a nearest neighbor search in the space of outcomes and taking the corresponding policy.

Running forward

|

Running backward

|

Falling

|

GEP-PG

After a few GEP episodes, the actions, states and rewards experienced are loaded into the replay buffer of DDPG. DDPG is then run with a randomly initialized actor and critic, but benefits from the content of this replay buffer.

DDPG fails on Continuous Mountain Car

Perhaps, the most surprising result of our study is that DDPG, which is considered as a state-of-the-art method in deep reinforcement learning with continuous actions, does not perform well on the very low dimensional Continuous Mountain Car benchmark, where simple exploration methods can easily find the goal.

In CMC, until the car reaches the top for the first time, the gradient of performance points towards standing still in order to avoid negative penalties corresponding to energy expenses. Thus, the gradient is deceptive as it drives the agent to a local optimum where the policy fails.

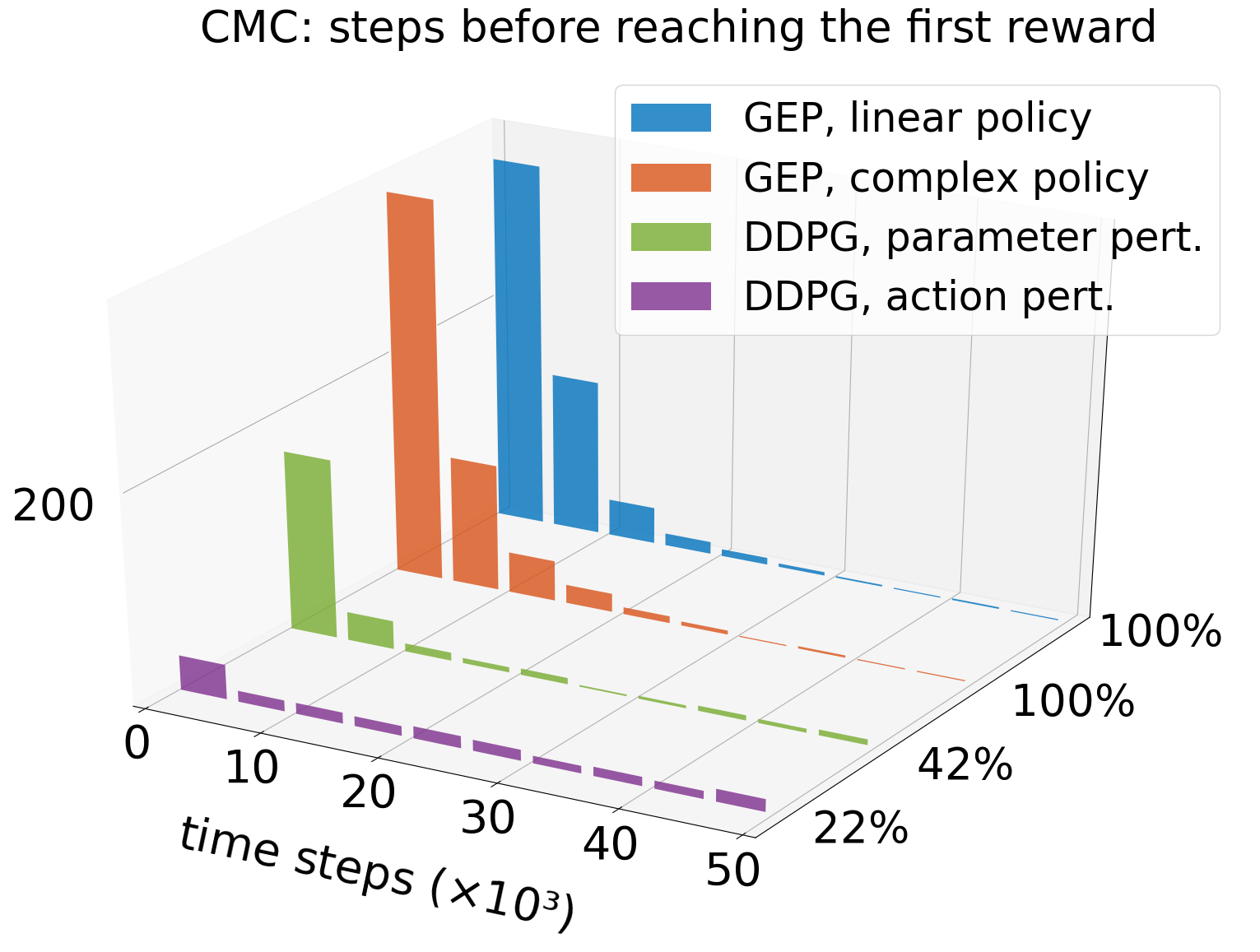

Below we show the effect of this deceptive gradient: the form of exploration used in DDPG can escape the local optimum by chance, but the average time to reach the goal for the first time is worse than one would get using purely random exploration. Using noise on the actions, DDPG finds the top in the first 50 episodes only 22% of the time. Using policy parameter perturbations, it happens 42% of the time. By contrast, because its exploration strategy is insensitive to the gradient of performance, GEP is good at quickly reaching the goal for the first time, no matter the complexity of the policy (either a simple linear policy or the same as DDPG).

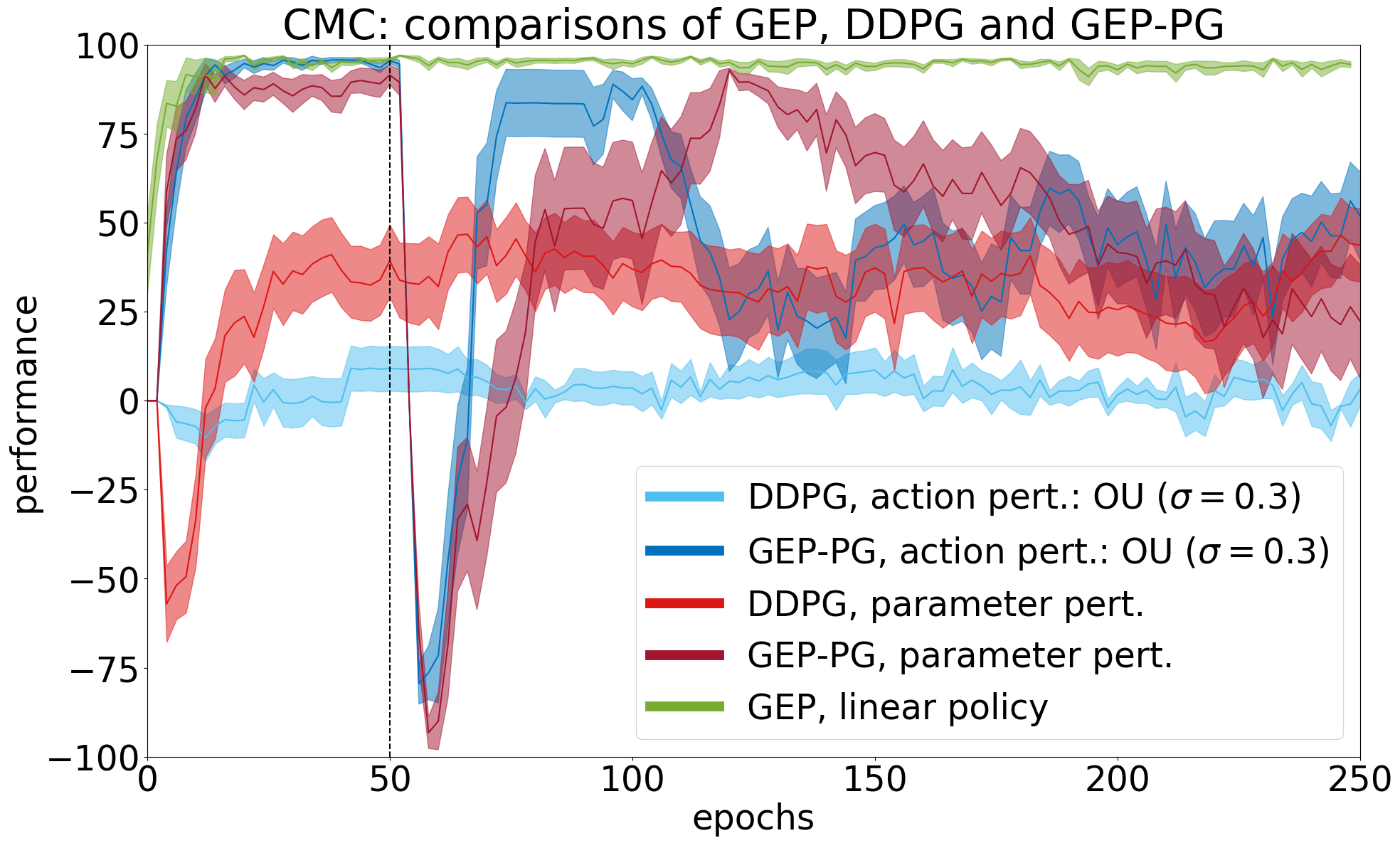

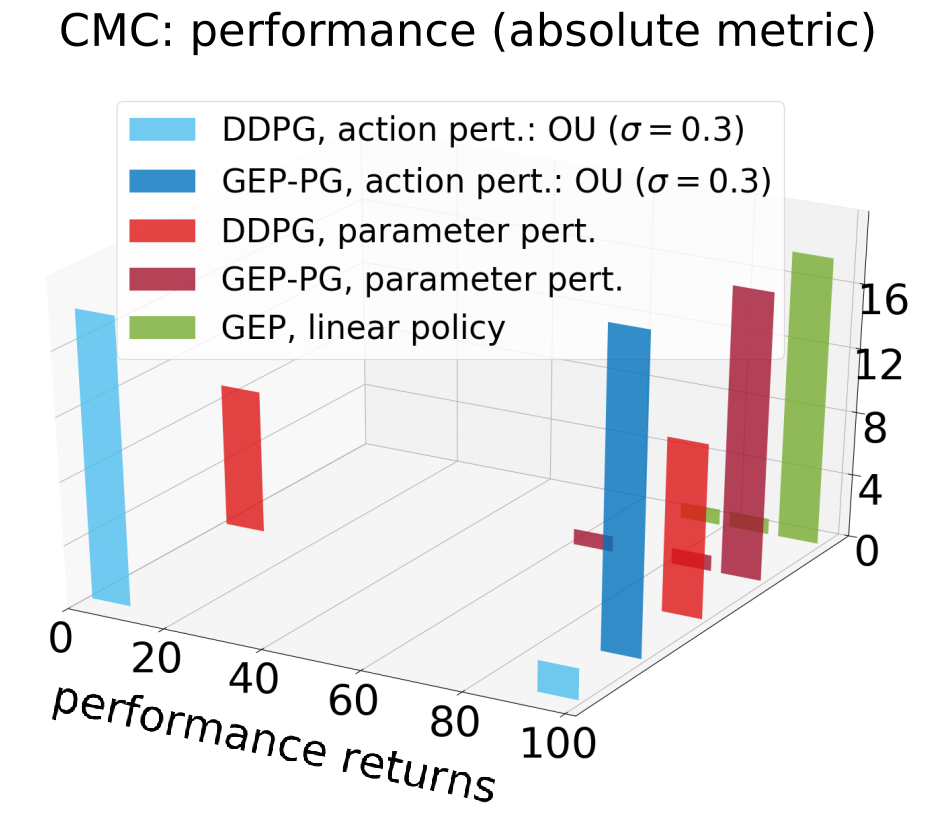

When filling the replay buffer of DDPG with GEP trajectories, good policies are found more consistently. It should be noted that although GEP-PG reached better performance than DDPG alone across learning (see histogram of the performances of best policies found across learning), it sometimes forgets them afterwards (see learning curves) due to known instabilities in DDPG [Henderson et al, 2017].

Learning curves - Continuous Mountain Car

|

Performance of best policies

|

GEP-PG obtains state-of-the-art results on Half-Cheetah

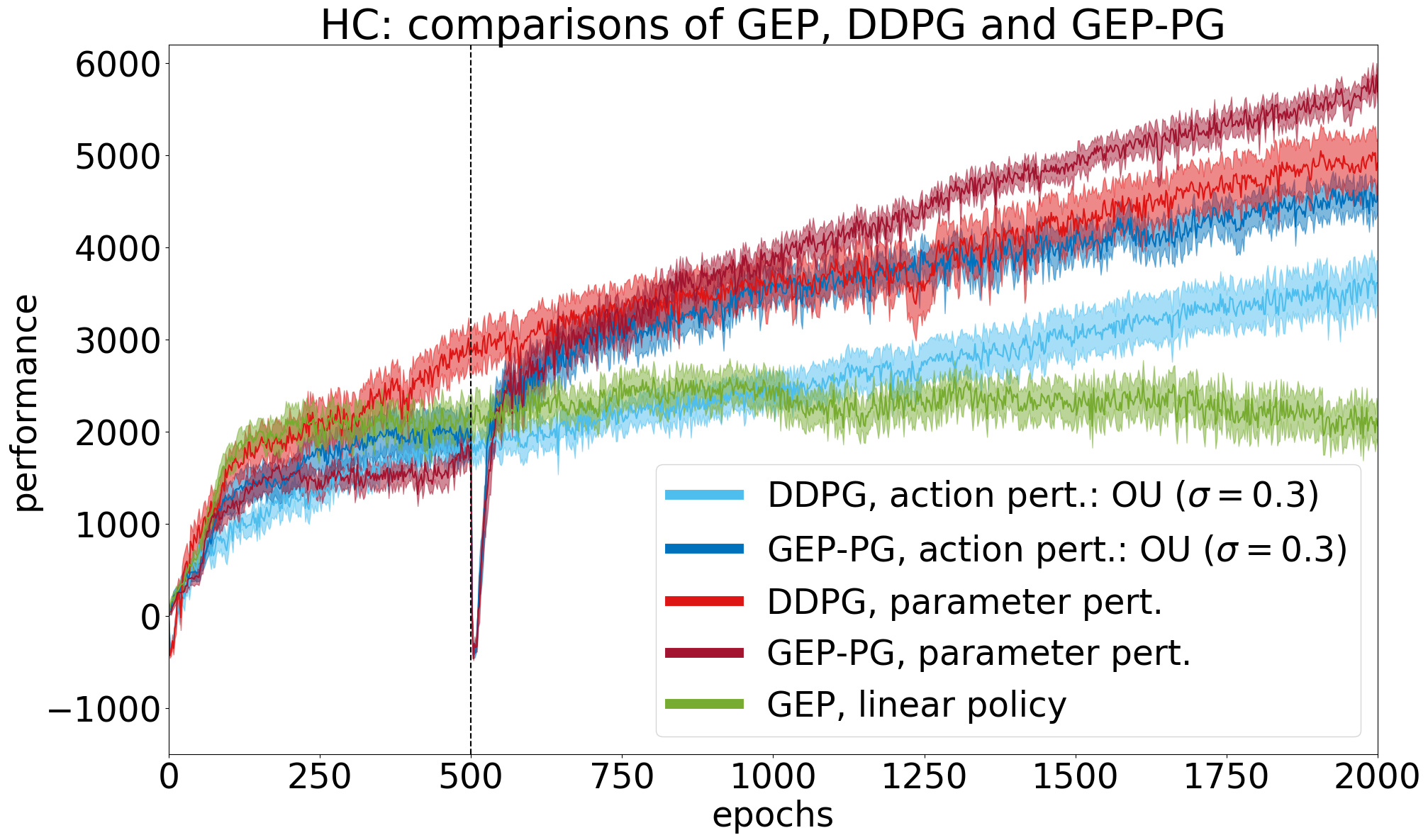

On the Half-Cheetah benchmark, GEP-PG runs 500 episodes of GEP then switches to one of two DDPG variants that we call action and parameter perturbation. The two GEP-PG variants (dark blue and red) significantly outperform their DDPG counterparts (light blue and red), and GEP alone (green). The variance of performance across different runs is also smaller in GEP-PG compared to DDPG alone.

Learning curves - Half-Cheetah

|

Good GEP-PG policy

|

What makes a good replay buffer

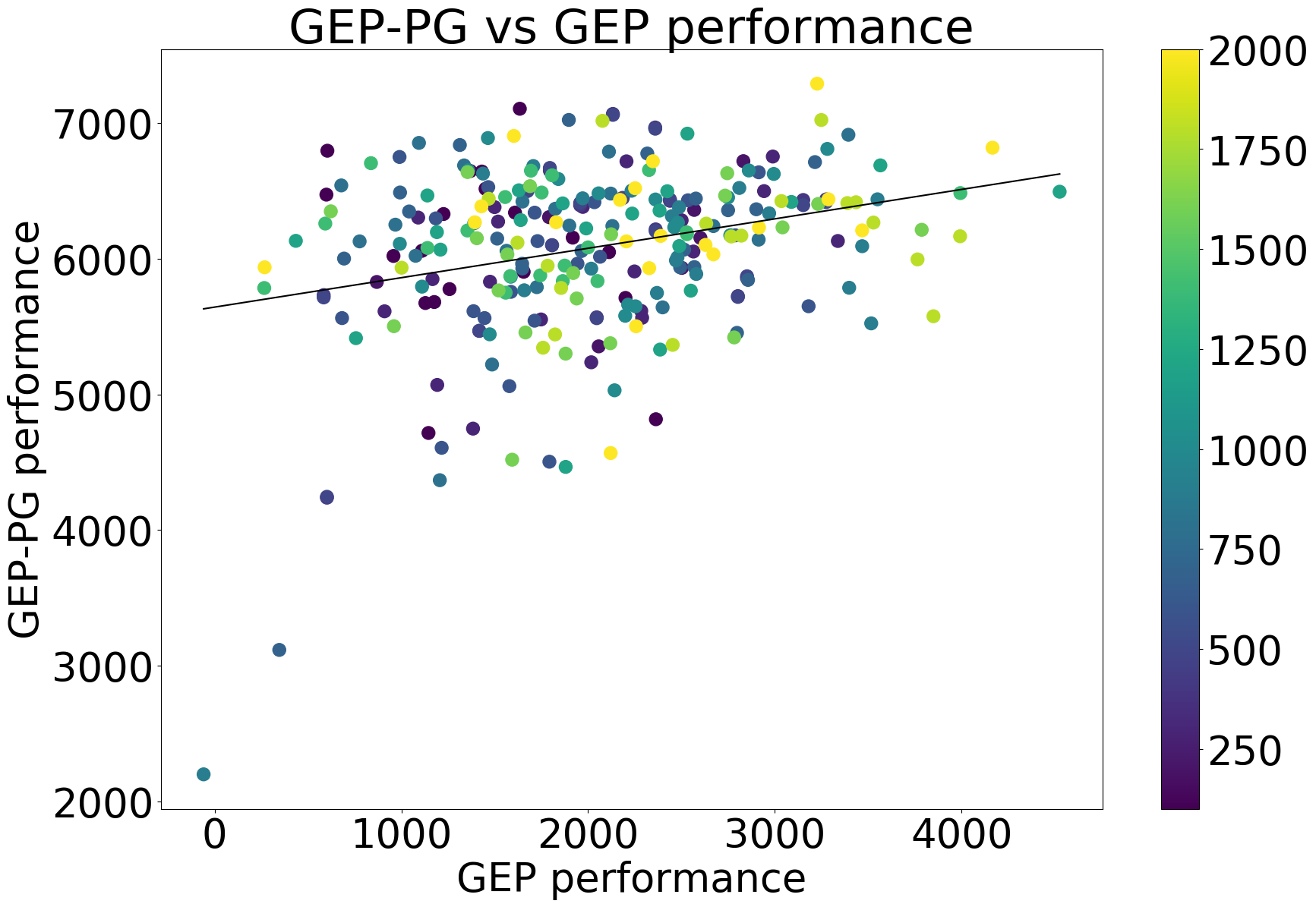

A question that remains unresolved is: what makes a good replay buffer? To answer it, we looked for potential correlations between the final performance of GEP-PG on Half-Cheetah and a list of other factors. We ran GEP-PG with various replay buffer sizes (100, 200, 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900, 1000, 1200, 1400, 1600, 1800, 2000 episodes) and a fixed budget for the DDPG part (1500 episodes). We found out that GEP-PG’s performance is not a function of the replay buffer size. Filling the replay buffer with 100 GEP episodes is enough to bootstrap DDPG. However, the quality and diversity of the replay buffer are important factors. We found that the performance of GEP-PG correlates significantly to the buffer’s quality:

- the final performance of GEP \((p<2\times10^{-6})\)

- the average performance of GEP during training \((p<4\times10^{-8})\)

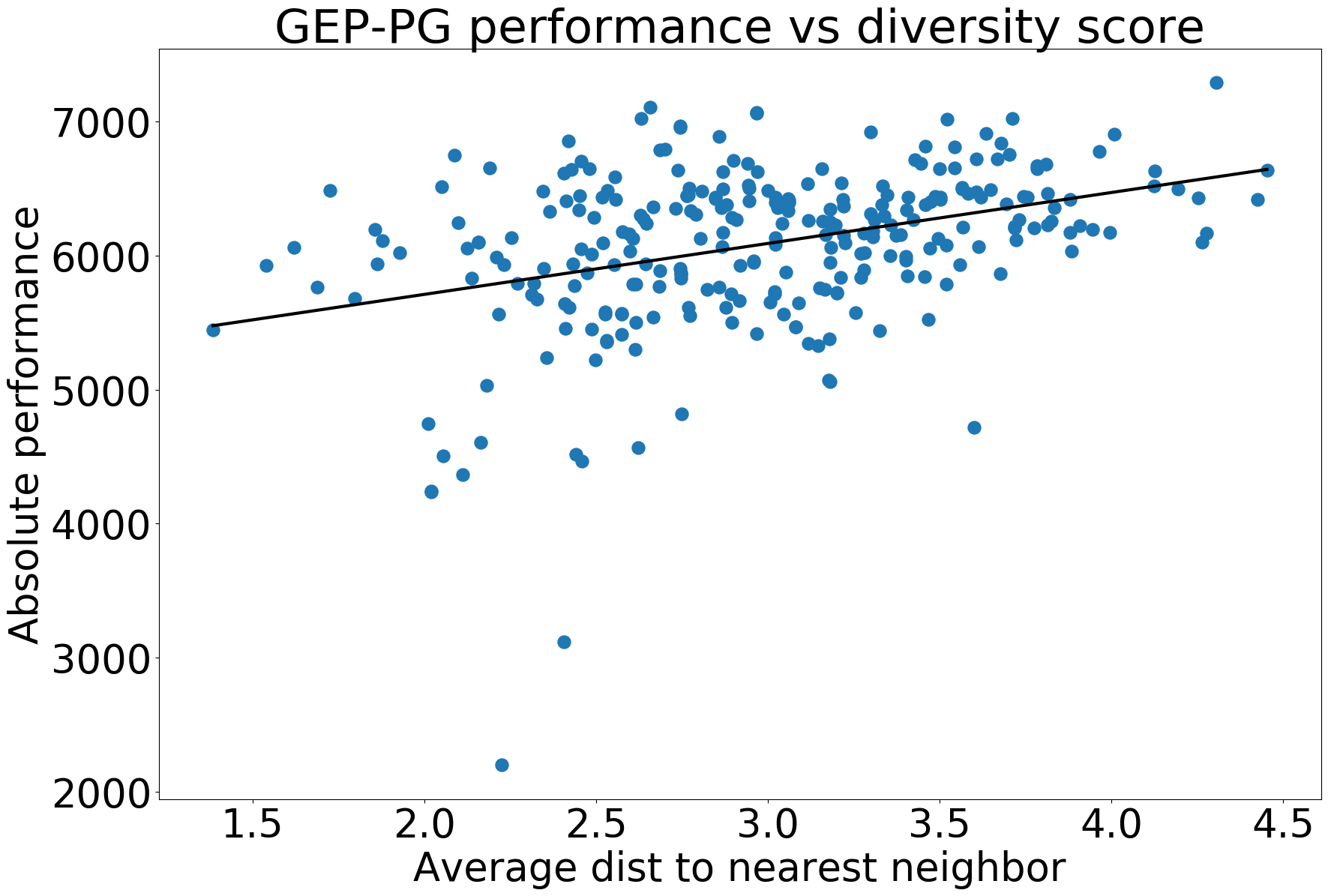

but also to the buffer’s diversity, as quantified by various measures:

- the standard deviation of the performances obtained by GEP during training. This measure quantifies the diversity of performances reached during training. \((p<3\times10^{-10})\)

- the standard deviation of the observation vectors averaged across dimensions. This quantifies the diversity of sensory inputs. \((p<3\times10^{-8})\)

- outcome diversity measured by the average distance to the k-nearest neighbors in outcome space (for various k). This measure is normalized by the average distance to the 1-nearest neighbor in the case of a uniform distribution, which makes it insensitive to the sample size. This is a measure of outcomes diversity. \((p<4\times10^{-10})\)

- the percentage of cells filled when the outcome space is discretized (with various number of cells). We also use a number of cells equal to the number of points, which make the measure insensitive to this number. This is a measure of outcomes diversity. \((p<4\times10^{-5})\)

- the discretized entropy with various number of cells. \((p<6\times10^{-7})\)

GEP-PG versus GEP performance, color represents the buffer size

|

GEP-PG performance versus diversity score

|

These correlations show that a good replay buffer should be both efficient and diverse (in terms of outcomes or observations). This means that implementing more efficient exploration strategies targeting these two objectives would likely further improve the performance of GEP-PG. GEP as used here, only aims at maximizing the diversity of outcomes. On the other hand, Quality-Diversity algorithms (e.g. MAP-Elites, Behavioral Repertoire Evolution) optimize for these two objectives, and could therefore prove to be strong candidates to replace GEP.

Future work

In our work, we have presented the general idea of decoupling exploration and exploitation in deep reinforcement learning algorithms and proposed a specific implementation of this idea using GEP and DDPG. In future work, we will investigate other implementations of this idea using different exploration algorithms (Novelty Search, MAP-Elites, BR-Evo or different gradient-based methods (ACKTR, SAC). More sophisticated implementations of IMGEP could also be used to improve the efficiency of exploration (e.g. curiosity-driven goal exploration or modular goal exploration).

Another aspect concerns the way GEP and DDPG are combined. Here, we studied the simplest possible combination: filling the replay buffer in DDPG with GEP trajectories. This way to transfer results in a drop in performance at switch time because DDPG starts from new randomly initialized actor and critic networks. In further work, we will try to avoid this drop by bootstrapping the actor network from GEP data at switch time. For instance, using the best GEP policy to generate (observation, action) samples from GEP trajectories, the DDPG actor network could be trained in a supervised manner. We could also call upon a multi-arm bandit paradigm to alternate between GEP and DDPG as required to maximize the learning efficiency, actively selecting the best learning strategy.

References

- Colas, C., Sigaud, O., & Oudeyer, P. Y. (2018). GEP-PG: Decoupling Exploration and Exploitation in Deep Reinforcement Learning Algorithms, ICML 2018 link

- Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Graves, A., Antonoglou, I., Wierstra, D., & Riedmiller, M. (2013). Playing atari with deep reinforcement learning. Nature link

- Silver, D., Huang, A., Maddison, C. J., Guez, A., Sifre, L., Van Den Driessche, G., … & Dieleman, S. (2016). Mastering the game of Go with deep neural networks and tree search. Nature, 529(7587), 484-489. link

- Lillicrap, T. P., Hunt, J. J., Pritzel, A., Heess, N., Erez, T., Tassa, Y., … & Wierstra, D. (2015). Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. ICLR 2016 link

- Bellemare, M., Srinivasan, S., Ostrovski, G., Schaul, T., Saxton, D., & Munos, R. (2016). Unifying count-based exploration and intrinsic motivation. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. 1471-1479). link

- Pathak, D., Agrawal, P., Efros, A. A., & Darrell, T. (2017, May). Curiosity-driven exploration by self-supervised prediction. In International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML) (Vol. 2017). link

- Lehman, J., & Stanley, K. O. (2011). Abandoning objectives: Evolution through the search for novelty alone. Evolutionary computation, 19(2), 189-223. Evolutionary Computation link

- Cully, A., & Demiris, Y. (2018). Quality and diversity optimization: A unifying modular framework. IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation, 22(2), 245-259. link

- Cully, A., Clune, J., Tarapore, D., & Mouret, J. B. (2015). Robots that can adapt like animals. Nature, 521(7553), 503. link

- Forestier, S., Mollard, Y., & Oudeyer, P.-Y. (2017). Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes with Automatic Curriculum Learning, 1–21. link

- Benureau, F. C., & Oudeyer, P. Y. (2016). Behavioral diversity generation in autonomous exploration through reuse of past experience. Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 3, 8.link

- Henderson, P., Islam, R., Bachman, P., Pineau, J., Precup, D., & Meger, D. (2017). Deep reinforcement learning that matters. arXiv preprint arXiv:1709.06560. AAAI 2018 link

- Plappert, M., Houthooft, R., Dhariwal, P., Sidor, S., Chen, R. Y., Chen, X., … & Andrychowicz, M. (2017). Parameter space noise for exploration. ICLR 2018 link

- Mouret, J. B., & Clune, J. (2015). Illuminating search spaces by mapping elites. link

- Cully, A., & Mouret, J. B. (2013, July). Behavioral repertoire learning in robotics. In Proceedings of the 15th annual conference on Genetic and evolutionary computation (pp. 175-182). ACM. link

- Wu, Y., Mansimov, E., Grosse, R. B., Liao, S., & Ba, J. (2017). Scalable trust-region method for deep reinforcement learning using Kronecker-factored approximation. In Advances in neural information processing systems (pp. 5285-5294). link

- Haarnoja, T., Zhou, A., Abbeel, P., & Levine, S. (2018). Soft Actor-Critic: Off-Policy Maximum Entropy Deep Reinforcement Learning with a Stochastic Actor. link

- Lopes, M., & Oudeyer, P. Y. (2012, November). The strategic student approach for life-long exploration and learning. In IEEE International Conference on Development and Learning and Epigenetic Robotics (ICDL), (pp. 1-8). link

- Nguyen, M., & Oudeyer, P. Y. (2012). Active choice of teachers, learning strategies and goals for a socially guided intrinsic motivation learner. Paladyn Journal of Behavioral Robotics, 3(3), 136-146. link

Contact

- Email: cedric.colas@inria.fr