This blog post presents our recent ICLR paper Language-biased image classification: evaluation based on semantic representations. The codebase accompanying this paper is available in the following repo.

Difficulty in interpreting functional mechanisms of a system

Humans tend to find human-like features in our daily life events. When winds blow a plastic bag on the street, children may feel like it is alive, known as animacy perception (Heider & Simmel, 1944; Scholl & Tremoulet, 2000; Tremoulet & Feldman, 2000). Artworks by Giuseppe Arcimboldo tell us that humans automatically detect human faces even if local components consist of objects unrelated to humans, like fruits or plants (Figure1A). Humans can also understand that other people have mental states like themselves, known as theory-of-mind (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985). These remarkable abilities enable us to read out someone’s subtle feelings and facilitate social communications in our daily life. However, they can get in the way when you interpret the behavior of an unknown system, e.g., when you are an AI researcher and would like to understand what representations are acquired in a machine learning model. You may unconsciously interpret a machine’s behavior as human-like from the similarity to daily human behaviors. But, it may be an overestimation due to our automatic prediction. We have to keep in mind that human interpretations tend to include a lot of expectations.

Recent machine learning models are trained using big data with massive parameters and achieve incredible performances for diverse tasks. Interpreting what representations are learned in these models is challenging due to their computational complexity. Even when you have a metric to evaluate system performance, quite different systems might output similar results for the metric. For example, in her ICLR 2022 keynote, Dr. Been Kim explained a clear example of the difficulty in interpreting machine learning models (the talk is available from this link) (Adebayo et al., 2018; Kim, 2022). The middle and right panels of Figure1B show saliency maps, which are metrics to explain which pixels machine learning models focus on when achieving an image classification task. Both saliency maps look similar and detect the main object of the photo, i.e., the bird. However, the right panel is actually the saliency map from an untrained network, while the middle one is from a trained network. This observation suggests that even when you see a visually meaningful output from a metric, you have to be cautious about interpreting the system.

Figure 1. (A) "Summer" by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (B) Saliency maps by trained and untrained networks (figure credit:

Been Kim, 2022, Beyond interpretability: developing a language to shape our relationships with AI(Kim, 2022),

link to blog)

Figure 1. (A) "Summer" by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (B) Saliency maps by trained and untrained networks (figure credit:

Been Kim, 2022, Beyond interpretability: developing a language to shape our relationships with AI(Kim, 2022),

link to blog)

Considering the difficulty in interpreting systems, how can we understand the learned representations of machine learning models? We think the literature on perceptual and cognitive sciences in humans and animals offers clues to this problem. No magical methodologies exist in these research fields to answer whether a machine learning model acquires human-like intelligence. Even so, these fields are sensitive to interpretation bias and have focused on trying to avoid over-interpretation or mis-interpretation. We believe these methodologies in the perceptual and cognitive science litterature could also help us understand the mechanisms, properties and functions of machine learning models.

Our recent paper at ICLR 2022 (Lemesle et al., 2022) follows this approach, aiming to evaluate machine learning models through the lens of cognitive science methodologies. Specifically, we conduct cognitive science experiments for machine learning models (Lupker, 1979; Rosinski, 1977) and analyze the models’ internal representation using neuroscience methodologies(Kriegeskorte et al., 2008). By applying this approach to a recent machine learning model, CLIP (Radford et al., 2021), jointly trained with texts and images, we find that the vision and language do not appropriately share semantic representations in the model. This finding is unexpected, given that the model has been successful in many recent language-vision tasks (Bau et al., 2021; Patashnik et al., 2021). Researchers may achieve to develop machine learning models with remarkably higher performances for some distributions of tasks in the future, but they also have to consider how to interpret them deeply.

A key feature of recent advances in machine learning models is to utilize a large size of language models, and many researchers attempt to apply the models to various tasks. In this blog post, we first introduce how language processing contributes to acquiring various abilities in humans and machine learning models. Then, we explain a phenomenon, picture-word interference, observed both in humans and models. We argue how we evaluate the mechanisms underlying picture-word interference in models in our ICLR paper. By importing cognitive science methodologies, we evaluate models in a controlled way. We suggest that such a strategy prevents us from overestimating artificial intelligence due to partial and surface similarity between humans and models.

Language as a tool to shape perception and cognition

Humans use language not only as a tool to communicate with each other but also to shape fundamental aspects of perception and cognition. For example, color categorization emerges even before infants’ language acquisition (Yang et al., 2016), but language acquisition reorganizes these color categorical representations (Franklin et al., 2008). Humans also share common semantic representations for vision and language in some brain regions. For example, Quiroga et al. 2009 recorded single-cell activities from human patients, implanted with intracranial electrodes for clinical reasons. They show that single neurons in the medial temporal lobe respond selectively to representations of the same individual across the visual portrait and its written name.

Similar to advantages in humans, language has benefits in building autonomous agents capable of acquiring diverse skills in open-ended environments. For the design of Vygotskian autotelic AIs, a novel perspective suggested by Colas et al., 2022, agents are immersed into and interact with rich socio-cultural worlds, and then they internalize physical and sociocultural interactions within themselves (for the details, see also the website). They use language as a cognitive tool that mediates stimulus and actions to imagine their own goals, and for planning, reasoning, and learning about them. For example, in the IMAGINE approach (Colas et al., 2020), a Vygotskian autotelic AI approach, agents receive language descriptions from a social partner about their behaviors, internalize these descriptions, and create new goals they have never experienced by leveraging the compositionality of the internalized language information.

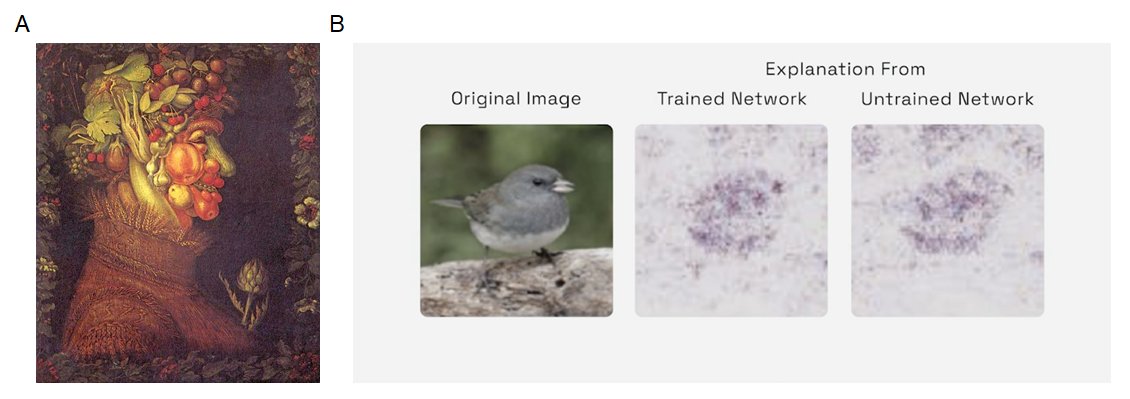

In addition, many joint learning models of language and vision have been reported recently. One prominent example is the CLIP (Contrastive Language–Image Pre-training) model reported by the OpenAI team (Radford et al., 2021), consisting of joint learning of language and vision, which we evaluated in our paper (Lemesle et al., 2022). It efficiently learns visual concepts from natural language supervision and can be applied to various visual tasks in a zero-shot manner.

Figure 2. Overview of the CLIP model. (figure credit: Alec Radford, et al., 2021, Learning Transferable Visual Models

From Natural Language Supervision (Radford et al., 2021),

link)

Figure 2. Overview of the CLIP model. (figure credit: Alec Radford, et al., 2021, Learning Transferable Visual Models

From Natural Language Supervision (Radford et al., 2021),

link)

The CLIP architecture consists of image and text encoders (Figure 2). These encoders are trained on a large dataset of image-text pairs with contrastive objectives, where they learn to align text and image representations for each pair (Figure 2, left). The pre-trained CLIP model can be used for various visual tasks. When applying the model for an image classification task (Figure 2, right), one uses the pre-trained text encoder to create a set of the embedding representations for classification labels by combining each label with a text prompt like “a photo of [label]”(Figure 2, (2)). For instance, for the labels “plane,” “car,” and “dog,” the text encoder outputs each embedding representation from the prompt “a photo of plane,” “a photo of car,” or “a photo of dog.” The pre-trained image encoder output the embedding representation for the input image (Figure 2, (3)). By computing the similarity of the image representation and each text label representation and selecting the highest similarity pair (e.g., the similarity between the image dog and text “a photo of dog”), the CLIP model can solve the image classification task in a zero-shot manner. Many applications of the CLIP model exist while combining the pre-trained model with other networks (Bau et al., 2021; Patashnik et al., 2021).

Picture word interference in humans and machines

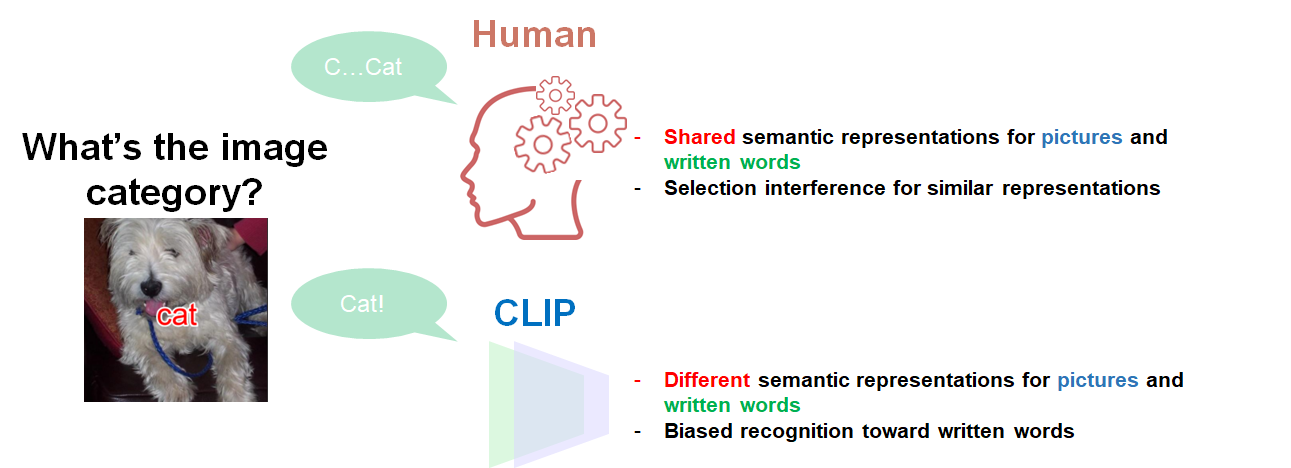

While language contributes to acquiring general visual abilities, its abstraction can produce biased recognition for humans. Picture word interference is such a phenomenon. When humans observe an image coupled with a word having a different meaning from the image, the image categorization is disturbed by the word (Figure 3) (Lupker, 1979; Rosinski, 1977). For example, when a human observes a “dog” image with the written word “cat,” the written word “cat” interferes with the reaction time to answer the image category “dog” and increases the error rate.

Figure 3. Picture-word interference in humans and machines. Summary of Yoann Lemesle, et al., (2022); Languagebiased image classification: evaluation based on semantic representations (

Lemesle et al., 2022)

Figure 3. Picture-word interference in humans and machines. Summary of Yoann Lemesle, et al., (2022); Languagebiased image classification: evaluation based on semantic representations (

Lemesle et al., 2022)

In particular, the interference effect is strong when the image category is similar to the superimposed word. The finding suggests that shared semantic representations of images and words disrupt image categorization. It has been considered that multiple mechanisms mediate this effect in humans. First, when a participant observes a word-superimposed image, an activation process synthesizes semantic representations corresponding to the superimposed word and picture. This semantic representation is shared for pictures and superimposed words, so when the word is semantically similar to the picture, these activations are similar to each other. Based on the representations, a selection process decides which possible activation is the answer for the current task. Since the activated representation is shared across words and pictures, these dual activations confuse the decision in the selection process.

Similar to humans, recent joint models of language and vision also show recognition interference. For example, while the CLIP model can have high image classification performances for natural images in a zero shot manner (Figure 2), it can also be disrupted by superimposing a written word on the image, called a typographic attack (Figure 3)(Goh et al., 2021). In the case of Figure 3, the CLIP model recognizes the word-superimposed image as the “cat” image category.

Joint multimodal representations are bound to be very useful in many contexts. Even when you obtain noisy information from one modality (e.g., finding parking by car on a rainy day), information from another modality (e.g., the written word ’parking”) helps what you see. Picture-word interference is a special case of the functionality showing negative side effects. Therefore, showing similar interference to humans in machine learning models might look like a good sign that they also acquire the generic skill. However, it’s unclear what interference in machines means. If picture-word interference in machine models is due to a simple bias toward language information while ignoring visual information, the interference can result only in negative side effects.

Surface performance similarity does not always mean identical underlying mechanisms

Both humans and the CLIP model show picture-word interference. Observing a few similar biases in a picture-word interference task may lead to believing the mechanisms are the same. But, the surface performance similarity by partial observations may be due to largely different underlying mechanisms. The lens of cognitive science methodologies tells us that we should conduct a systematic, structured examination of the biases. Our study investigates this and shows that different functional mechanisms mediate picture-word interference in humans and the CLIP model (Figure 3).

Figure 4. Overview of our benchmark test.

Figure 4. Overview of our benchmark test.

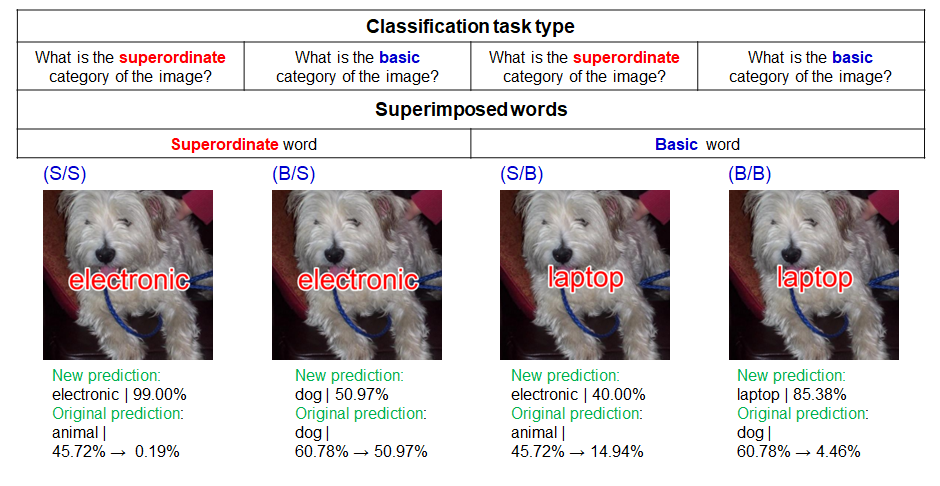

We first focused on the fact that human picture-word interference depends on the semantic relationship between images and written words. Cognitive science works show that the interference effect of written words on the image classification is larger when the image category is semantically similar to the word one (e.g., a written word “cat” for a “dog” image) (Rosinski, 1977). We imported this experimental paradigm for machine learning models and created the picture-word image dataset, in which we controlled the semantic categories between images and written words (Figure 4). Our dataset consists of a combination of natural image datasets and hierarchical superordinate/basic word labels. Our benchmark test is a 2 x 2 block design. One condition is the classification task type, indicating what is the image category level to be answered. The category level is superordinate (e.g., “animal,” “furniture”) or basic (“dog,” “cat”). The other condition is the superimposed word category level, superordinate or basic. In total, there are four conditions as follows.

- The superordinate image classification for the superordinate word embedding (S/S).

- The basic image classification for the superordinate word embedding (B/S).

- The superordinate image classification for the basic word embedding (S/B).

- The basic image classification for the basic word embedding (B/B).

We evaluated the CLIP model using the benchmark test. We showed that language-biased classification in the CLIP model does not depend on the semantic relationship between images and written words, although superimposing written words on images strongly biased the image classification to the written word category. The finding suggests that even when we observe picture-word interference in the CLIP model, the way to process the semantics of images and written words is different from humans.

To further explore what representations are acquired in the CLIP, we imported a neuroscience methodology tool, Representational Similarity Analysis (RSA) (Kriegeskorte et al., 2008), and investigated what is represented in the CLIP image encoder for word-superimposed images. RSA refers to an image-by-image similarity assessment of intermediate representations in a brain or model. By computing the representational similarity of images, one can understand which internal activations are similar. Through the analysis of images and written words, we found that the CLIP image encoder represents the neural representation of written words different from that of visual images (For example, the neural representation of a written dog is different from a visual dog image). Consistent results are also recently reported in another study (Materzynska et al., 2022).

Our study shows that the CLIP model does not have a common representation of language and vision, and the image classification is strongly biased toward written words (Figure 3). In this study, we imported cognitive science methodology to evaluate the models in a controlled manner. This approach prevents us from overestimating artificial intelligence due to partial performance similarity between humans and models.

Analogous to our picture-word interference example, previous works in comparative studies of humans and machines also see that interpretation from partial observations can lead to misunderstanding the underlying mechanisms of machine learning models and that we need to resist human interpretation bias (reviewed by Funke et al., 2021). For example, feedforward convolutional neural networks show high accuracies comparable to human performance in an image classification task. Although the classification accuracy is similar between humans and models, Geirhos et al. 2019 show that the models rely on texture features of an image, whereas humans rely on shape features, by conducting psychophysical experiments for humans and models.

In the future, people will expect more from artificial intelligence capabilities. The expectation can cause overestimations when interpreting the functional mechanisms of artificial intelligence. We may achieve to develop artificial intelligence showing remarkably higher performances for some distributions of tasks in the future. However, we cannot judge how generic they are without a strict way of interpreting them. We will need to further explore methodologies about how to interpret them.

Cite this blog post

@misc{sawayama:hal-03729242,

TITLE = ,

AUTHOR = {Sawayama, Masataka and Lemesle, Yoann and Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves},

URL = {https://developmentalsystems.org/watch_ai_through_cogsci},

YEAR = {2022},

MONTH = July,

HAL_ID = {hal-03729242},

HAL_VERSION = {v1},

}

Cite our ICLR 2022 paper

@inproceedings{lemesle2021evaluating,

title={Language-biased image classification: evaluation based on semantic representations},

author={Lemesle, Yoann and Sawayama, Masataka and Valle-Perez, Guillermo and Adolphe, Maxime and Sauz{\'e}on, H{\'e}l{\`e}ne and Oudeyer, Pierre-Yves},

booktitle={International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR)},

year={2022}

}