Teaching algorithms are becoming a key ingredient to scaffold Deep RL agents into their learning odyssey, leading to policies that can generalize to multiple environments. This blog presents this emerging Deep RL sub-field and showcases recent work done in the Flowers Lab on designing a Learning Progress based teacher algorithm.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Building Deep RL agents that generalize. Leveraging advances in both training procedures and scalability, the Deep Reinforcement Learning community is now able to tackle ever more challenging control problems. This dynamic is shifting the sets of environments that are considered by researchers for benchmarking, leading to a drift from simple deterministic environments towards complex, more stochastic alternatives. This shift is key if we want to bring Deep RL outside of the lab, where robustness and generalization to previously unseen changes of the environment is essential for successful operation.

Training in procedurally generated environment. One emerging method as a step towards this objective is to train Deep RL agents on proceduraly generated environments and assess whether the considered approach is able to generalize to the space of possible environments. In Open AI’s paper Quantifying Generalization in Reinforcement Learning, authors present CoinRun, a mario-like platform game whose levels are proceduraly generated. They show that increasing the training set of proceduraly generated levels directly correlates with an increase in test-time performances on previously unseen levels, showing that training diversity is key for generalization.

Links with domain randomization. Similar procedures (termed Domain Randomization) have also been used as a way to enable Sim2Real transfer, which recently led to the training of a Deep RL agent able to robustly solve a Rubik’s cube with a real-world robotic hand, leveraging intensive training in simulation. To facilitate the development and comparative analysis of Deep RL algorithms that generalize, propositions of benchmark environments emerges from the community, such as Open AI’s ProcGen, a suite of 16 procedural 2D games, or Unity’s Obstacle Tower Challenge, a complex 3D procedural escape game. However, a limitation of these benchmarks is that they do not allow to study whether the ability to control the procedural generation can be beneficial for training Deep RL agents.

Teacher algorithms that dynamically adapt the distribution of procedurally generated environments. Given such a possibility, how can a teacher algorithm control the sequence of training environments enabling a Deep RL agent to acquire fastly skills that generalize to many environments? A simple approach is to propose randomly generated environments. If the amount of unfeasible environments from the set is not too high for the given learner, this might work reasonably well (as in CoinRun). But for more challenging scenarios, one would need smarter training strategies that avoid proposing too easy or too difficult environments, while ensuring forgetting does not happen. This brings us in the domain of Curriculum Learning (CL).

Automated Curriculum Learning. Given enough time and expert knowledge on the given benchmark, one could design a learning curriculum tailored for the considered learner. This is likely to work well, however, for real-world applications of Deep RL, it might be interesting to try to relax the time (i.e money) and expert knowledge (i.e money) required to design the curriculum. And there might also be cases where acquiring expert knowledge is not possible (as when choosing tasks from a task space embedding learned online). One more versatile approach which alleviates this need for domain knowledge is to rely on Automatic Curriculum Learning.

In our recent CoRL 2019 paper, we propose such an approach based on the use of Absolute Learning Progress as a signal to organise the curriculum. We frame this generalization challenge as a Strategic Student problem, formalizing a setting where one has to sequentially select distributions of environments to train on, and where the objective is to maximize average competence over the whole space of environments after a given number of interactions. Importantly, we explicitly do not assume to know the learnable subset of environments that can be generated, and we consider the learner as a black-box whose abilites are unknown. Thus, a teacher algorithm needs to incrementally learn a model of how the Deep RL agent performs in various parameterized environments, and to use this model to organize the learning curriculum.

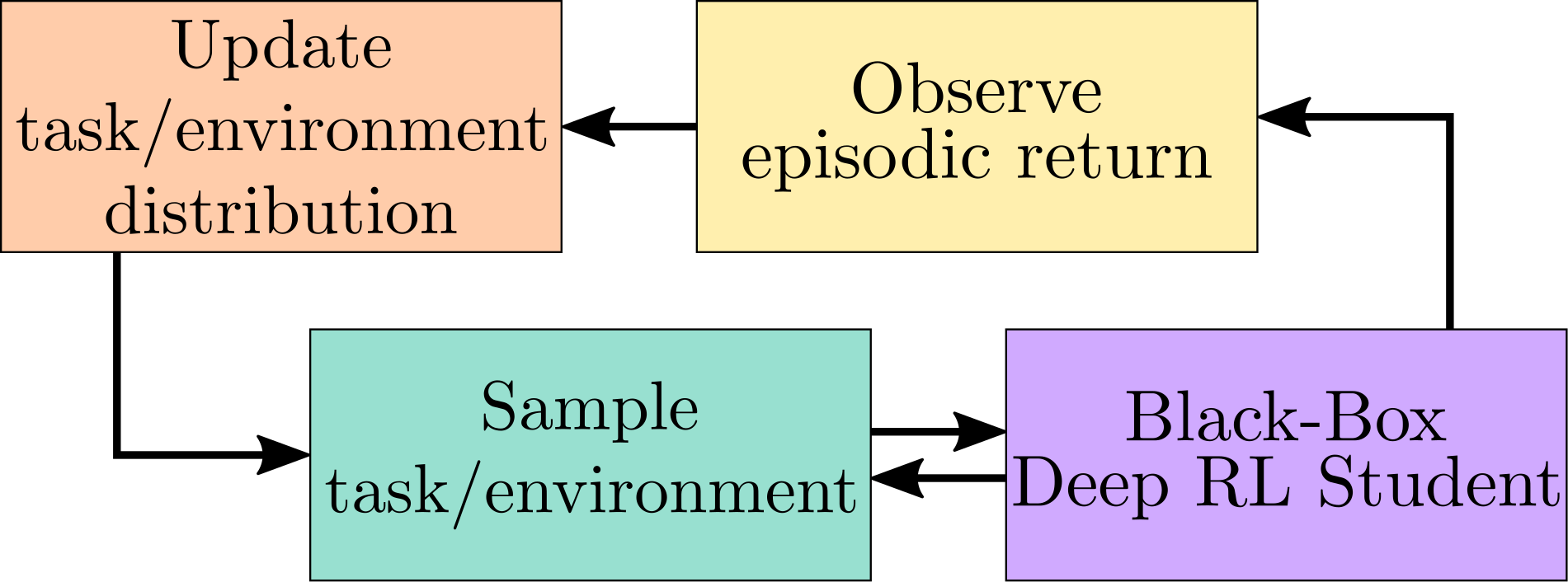

The Continuous Teacher-Student Framework

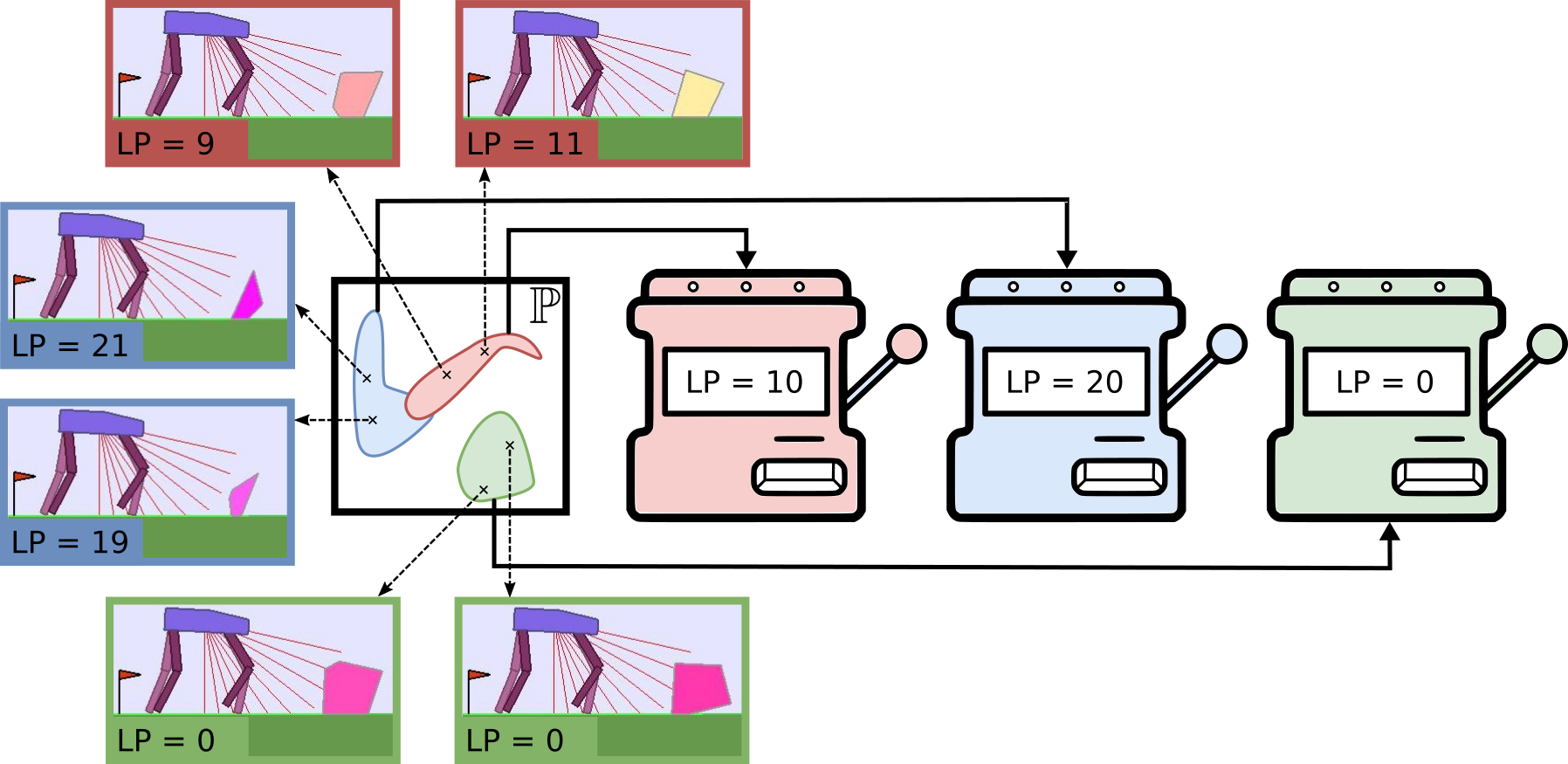

This Continuous Teacher-Student framework, depicted above, enables us to address the “curriculum generation towards generalization” problem. The Teacher algorithm samples an environment (i.e a parameter vector given to the procedural generation engine) from its current environment distribution, proposes it to its Deep RL Student, observes the associated episodic reward and updates its sampling distribution accordingly. Importantly, the Student is considered as a Black-Box, meaning that the Teacher does not have access to its internal state and does not know its learning mechanisms, making this approach applicable to any learning system. Likewise, to extend this approach to a wide range of scenarii, we do not assume to have expert knowledge on the environment space (aka parameter space) , and therefore assume that it could contain unfeasible subspaces, irrelevant dimensions and non-linear difficulty gradients.

Learning-Progress based Teacher algorithms

The learning signal used to organize a learning curriculum is absolute learning progress. This learning signal was extensively studied as a theoretical hypothesis to explain why and how human babies spontaneously explore, i.e. as a model of human curiosity-driven learning. It operationalizes the general idea (formulated by many psychologists) that humans are intrinsically motivated to explore environments of optimal difficulty, neither too hard nor too easy. Indeed, various models showed that exploration driven by an LP-based intrinsic reward self-organizes learning curriculum of increasing complexity, for e.g. reproducing the developmental progression of vocalisations or tool use in infants.

Following this insight, LP was later applied to automate curriculum learning for efficient learning of skills in robots. For example, RIAC and Covar-GMM are two curriculum learning algorithms for continuous environment spaces that were paired with simple population-based DMP controllers. In both approaches, the sequential task selection problem is transformed into an EXP4 Multi-Armed Bandit (MAB) setup in which arms are dynamically mapped to subspaces of the task/environment space, and whose utilities are defined using a local LP measure. The objective is then to optimally select on which subspace to sample an environment in order to maximize LP. In RIAC, arms are defined as hyperboxes over the environment space, their utility is the difference of reward between old and recent environments sampled from the hyperbox. In Covar-GMM, the arms of the MAB are gaussians from a Gaussian Mixture Model. The GMM is periodically fited on tuples composed of an environment’s parameter vector concatenated to its associated reward (obtained by the student) and its relative time value.

ALP-GMM

Building up on Covar-GMM, we propose Absolute Learning Progress Gaussian Mixture Model (ALP-GMM), a variant based on a richer ALP measure capturing long-term progress variations that is well-suited for RL setups. ALP gives a richer signal than (positive) LP as it enables the teacher to detect when a student is losing competence on a previously mastered environment subspace (thus preventing catastrophic forgetting, which is a well-known issue in DRL).

The key concept of ALP-GMM is to fit a GMM on a dataset of previously sampled environment’s parameters (parameters for short) concatenated to their respective ALP measure. Thus, each gaussian groups environments sampled so far according to a similarity that depends both on their physical features and the corresponding ALP of the Deep RL agent. Then, the Gaussian from which to sample a new parameter is chosen using an EXP4 bandit scheme where each Gaussian is viewed as an arm, and ALP is its utility. This enables the teacher to bias the parameter sampling towards high-ALP subspaces. To get this per-parameter ALP value, we take inspiration from previous work on developmental robotics: for each newly sampled parameter $p_{new}$ and associated episodic reward $r_{new}$, the closest (Euclidean distance) previously sampled parameter $p_{old}$ (with associated episodic reward $r_{old}$) is retrieved using a nearest neighbor algorithm. We then have $alp_{new} = |r_{new} - r_{old}|$.

The GMM is fit periodically on a window $\mathcal{W}$ containing only the most recent parameter-ALP pairs (here the last $ 250 $) to bound its time complexity and make it more sensitive to recent high-ALP subspaces. The number of Gaussians is adapted online by fitting multiple GMMs (here having from $2$ to $k_{max}=10$ Gaussians) and keeping the best one based on Akaike’s Information Criterion. Note that the nearest neighbor computation of per-parameter ALP uses a database that contains all previously sampled parameters and associated episodic rewards, which prevents any forgetting of long-term progress. In addition to its main environment sampling strategy, ALP-GMM also samples random parameters to enable exploration (here $p_{rnd}=20%$).

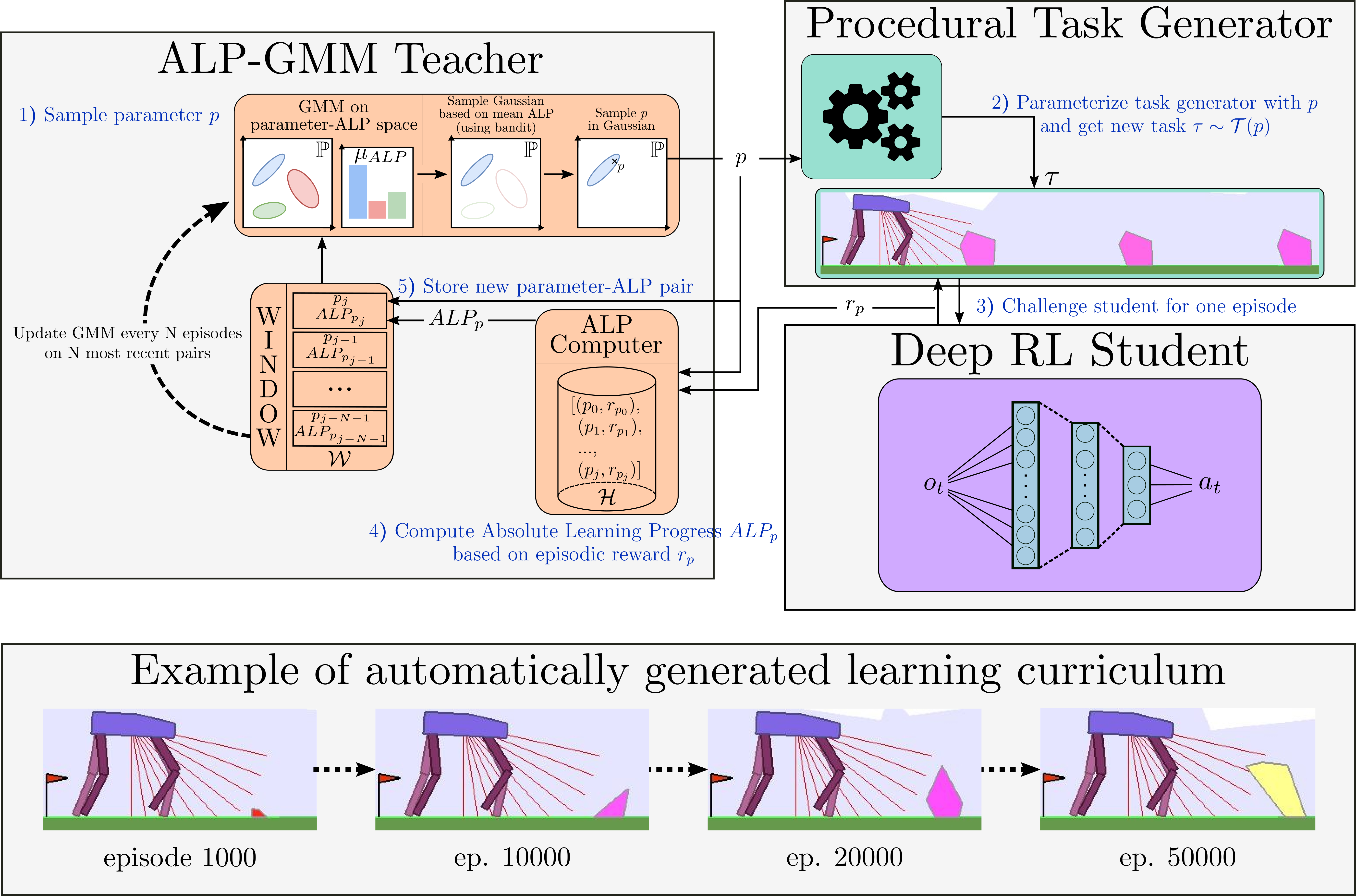

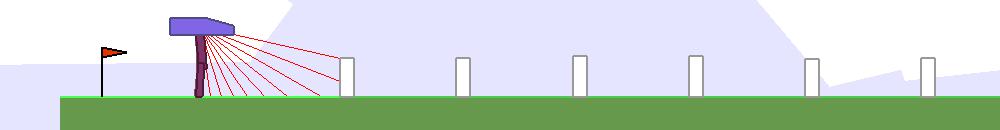

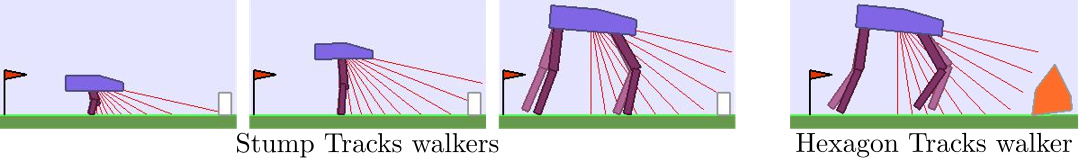

Procedurally Generated BipedalWalker Environments

The BipedalWalker environment offers a convenient test-bed for continuous control, allowing to easily build parametric variations of the original version (controlling changes in walker morphology or walking track layout). The learning agent, embodied in a bipedal walker, receives positive rewards for moving forward and penalties for torque usage and angular head movements. Agents are allowed up to $ 2000 $ steps to reach the other side of the map. Episodes are aborted with a reward penalty if the walker’s head touches an obstacle or the ground.

To study the ability of our teachers to guide DRL students, we design two continuously parameterized BipedalWalker environments enabling the procedural generation of walking tracks:

| Stump Tracks | Hexagon Tracks |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| A 2D parametric environment producing tracks paved with stumps varying by their height and spacing. | A more challenging 12D variation whose parameters are used to generate arbitrary hexagons. |

All of the experiments done in these environments were performed using OpenAI’s implementation of Soft-Actor Critic (SAC) as the single student algorithm. To test our teachers’ robustness to students with varying abilities, we use $ 3 $ different walker morphologies:

In addition to the default

bipedal walker morphology, we designed a bipedal walker with 50% shorter legs and a

bigger quadrupedal walker. We test all three walker types on Stump Tracks. The quadrupedal walker is also tested in Hexagon Tracks.

In addition to the default

bipedal walker morphology, we designed a bipedal walker with 50% shorter legs and a

bigger quadrupedal walker. We test all three walker types on Stump Tracks. The quadrupedal walker is also tested in Hexagon Tracks. Experiments

ALP-GMM generates student-specific curricula

The following videos provide visualizations of the environment sampling trajectory observed in a representative ALP-GMM run when paired with a short (left), default (middle) and quadrupedal (right) walker. In each frame, blue shades represent the Gaussians of the current mixture while dots represent sampled environments.

|

|

|

For each walker type one can observe that the curriculum generated by ALP-GMM starts with a random sampling phase (different in length depending on the walker type), which is due to the initial absence of progress of its student. Initial progress is then always detected on the leftmost part of the environment’s parameter space, which correspond to environments with low stump heights. Then, one can see that curricula generated by ALP-GMM significantly diverge depending on the walker type as it is adapted to their unique learning abilities. One can see that the more competent the walker, the more the sampling gradually shifts towards high-stump environments across time.

A single run of ALP-GMM allows to train Soft Actor-Critic controllers to master a wide range of track distributions. Here are examples of learned walking gates for short (left), default (middle) and quadrupedal (right) walkers ($1$ column = $1$ run):

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Comparative study on Stump Tracks

To analyze the impact of ALP-GMM teachers on student training, we compare it to RIAC, Covar-GMM and two reference algorithms:

-

Random Environment Curriculum (Random) - In Random, parameters are sampled randomly in the parameter space for each new episode. Although simplistic, similar approaches in previous work proved to be competitive against more elaborate forms of CL.

-

Oracle - A hand-constructed approach, sampling random environment distributions in a fixed-size sliding window on the parameter space. This window is initially set to the easiest area of the parameter space and is then slowly moved towards complex ones, with difficulty increments only happening if a minimum average performance is reached. Expert knowledge is used to find the dimensions of the window, the amplitude and direction of increments, and the average performance threshold.

For each condition we perform $ 32 $ seeded runs with each of our $ 3 $ students and periodically measure performance as the percentage of mastered environments ($ r > 230 $) of a fixed test set ($ n = 50$).

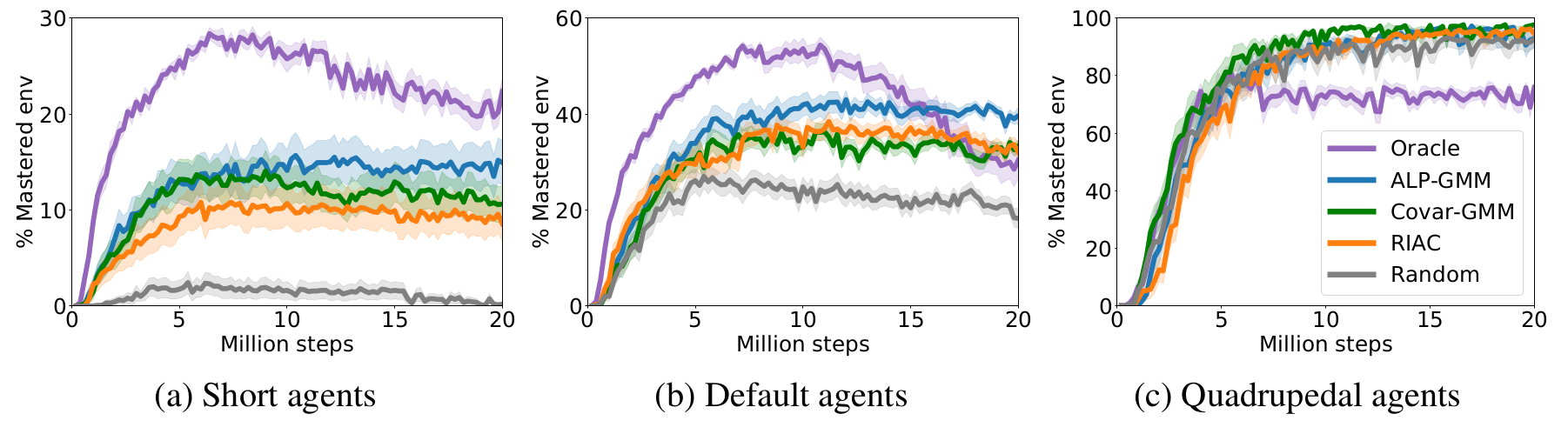

Evolution of mastered track distributions for Teacher-Student approaches in Stump Tracks. The mean performance (32 seeded runs) is plotted with shaded areas representing the standard error of the mean.

Evolution of mastered track distributions for Teacher-Student approaches in Stump Tracks. The mean performance (32 seeded runs) is plotted with shaded areas representing the standard error of the mean.

|

The figure above shows learning curves for each condition paired with short (a), default (b) and quadrupedal (c) walkers. First of all, for short agents, one can see that Oracle is the best performing algorithm, mastering more than $20$% of the test set after $20$ Million steps. This is an expected result as Oracle knows where to sample simple track distributions, which is crucial when most of the parameter space is unfeasible, as is the case with short agents. ALP-GMM is the LP-based teacher with highest final mean performance, reaching $14.9$% against $10.6$% for Covar-GMM and $8.6$% for RIAC. This performance advantage for ALP-GMM is statistically significant when compared to RIAC (Welch’s t-test at 20M steps: $p<0.04$), however there is no statistically significant difference with Covar-GMM ($p=0.16$). All LP-based teachers are significantly superior to Random ($p<0.001$). For details on how to use statistical tests for Deep RL, check this blog.

Regarding default bipedal walkers, our hand-made curriculum (Oracle) performs better than other approaches for the first $10$ Million steps and then rapidly decreases to end up with a performance comparable to RIAC and Covar-GMM. All LP-based conditions end up with a final mean performance statistically superior to Random ($p<10^{-4}$). ALP-GMM is the highest performing algorithm, significantly superior to Oracle ($p<0.04$), RIAC ($p<0.01$) and Covar-GMM ($p<0.01$).

For quadrupedal walkers, Random, ALP-GMM, Covar-GMM and RIAC agents quickly learn to master nearly $100$% of the test set, without significant differences apart from Covar-GMM being superior to RIAC ($p<0.01$). This indicates that, for this agent type, the parameter space of Stump Tracks is simple enough that trying random tracks for each new episode is a sufficient curriculum learning strategy. Oracle teachers perform significantly worse than any other method ($p<10^{-5}$).

Through this analysis we showed how ALP-GMM, Covar-GMM and RIAC, without strong assumptions on the environment, managed to scaffold the learning of multiple students better than Random. Interestingly, ALP-GMM outperformed Oracle with default agents, and RIAC, Covar-GMM and ALP-GMM surpassed Oracle with the quadrupedal agent, despite its advantageous use of domain knowledge. This indicates that training only on track distributions sampled from a sliding window that end up on the most difficult parameter subspace leads to forgetting of simpler environment distributions. Our approaches avoid this issue through efficient tracking of their students’ learning progress.

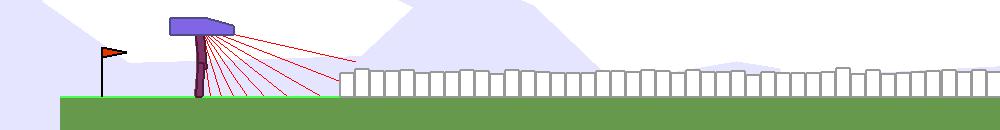

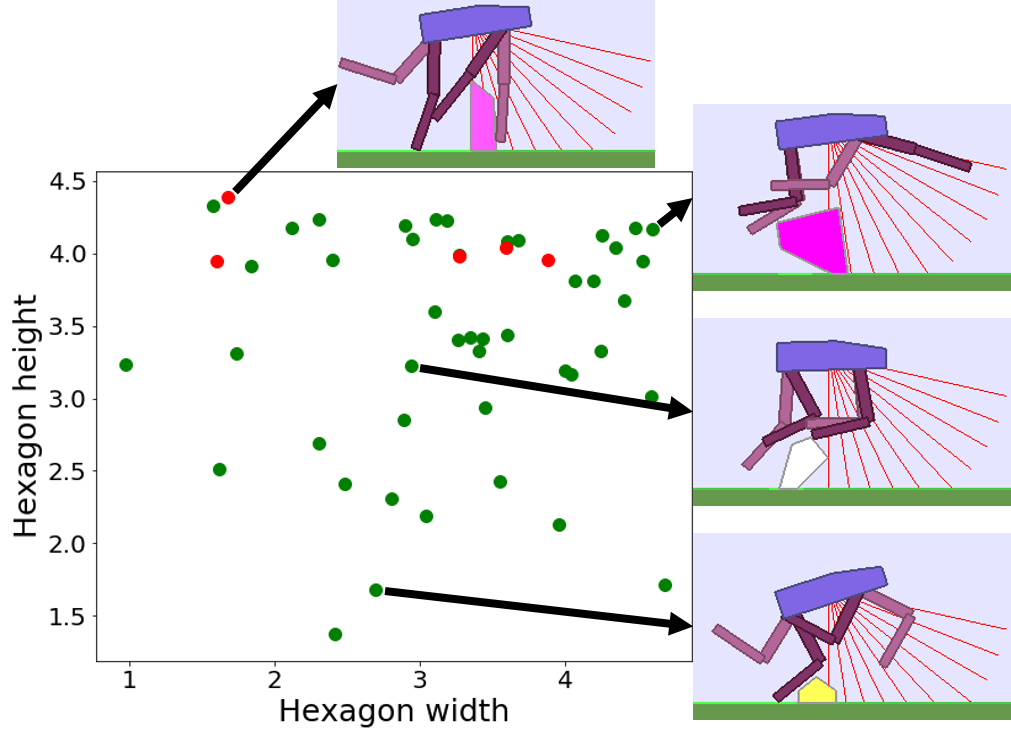

Comparative study on Hexagon Tracks, our environment with a 12-D parameter space

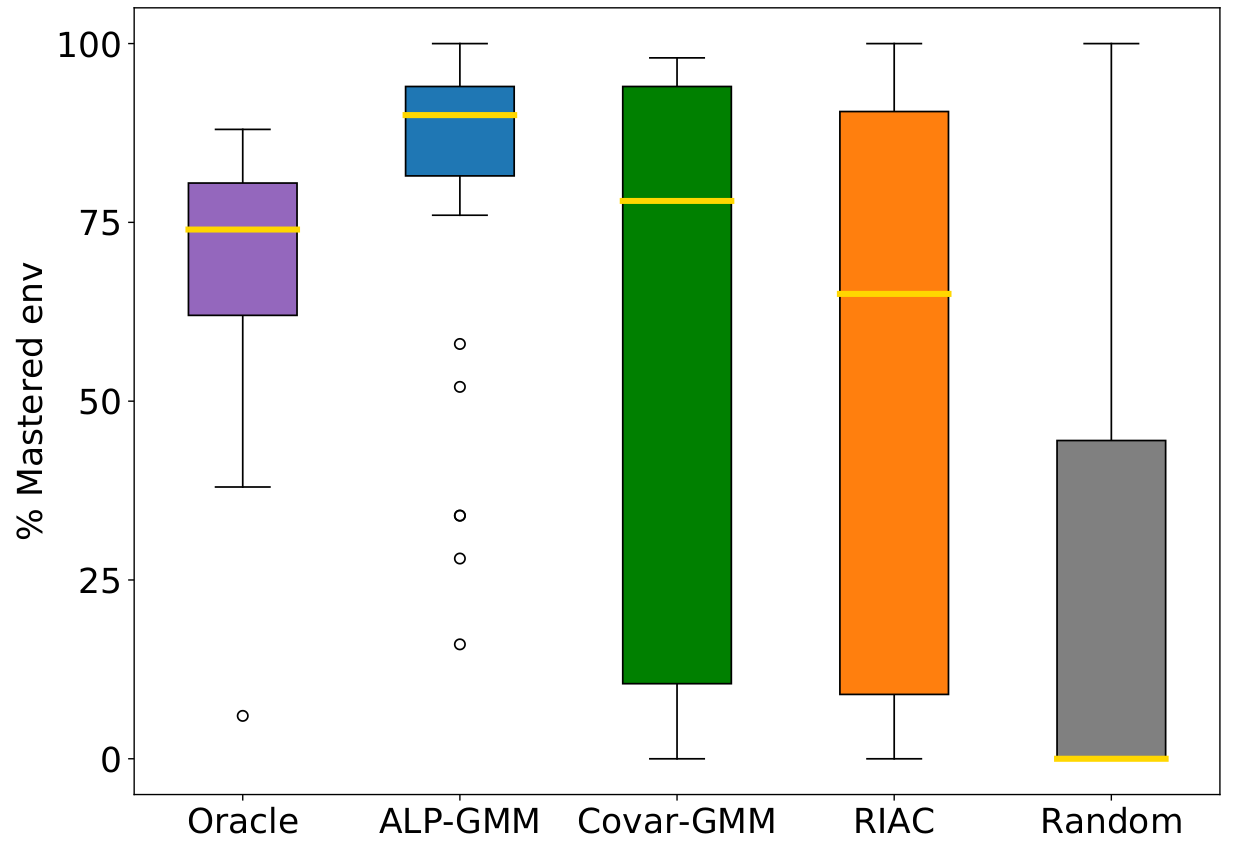

To assess whether ALP-GMM is able to scale to parameter spaces of higher dimensionality, containing irrelevant dimensions, and whose difficulty gradients are non-linear, we performed experiments with quadrupedal walkers on Hexagon Tracks, our 12-dimensional parametric BipedalWalker environment.

We analyzed the distributions of the percentage of mastered environments of the test set after training for $80$ Millions (environment) steps, depicted in the figure below (left plot). One can see that ALP-GMM both has the highest median performance and narrowest distribution. Out of the $32$ repeats, only Oracle and ALP-GMM always end-up with positive final performance scores whereas Covar-GMM, RIAC and Random end-up with $0%$ performance in $8/32$, $5/32$ and $16/25$ runs, respectively. Interestingly, in all repeats of any condition, the student manages to master part of the test set at some point (i.e non-zero performance), meaning that runs that end-up with $0%$ final test performance actually experienced catastrophic forgetting. This showcase the ability of ALP-GMM to avoid this forgetting issue through efficient tracking of its student’s absolute learning progress.

|

|

| In addition to the default bipedal walker morphology, we designed a bipedal walker with 50% shorter legs and a bigger quadrupedal walker. We test all three walker types on Stump Tracks. The quadrupedal walker is also tested in Hexagon Tracks. | Final performance of each condition run on Hexagon Tracks after 80M steps. Gold lines are medians, surrounded by a box showing the first and third quartile, which are then followed by whiskers extending to the last datapoint or 1.5 times the inter-quartile range. Beyond the whiskers are outlier datapoints. |

The following videos shows walking gates learned in a single ALP-GMM run.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In comparison, when using Random curriculum, most runs end-up with bad performances, like this one:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussion

This work demonstrated that ALP-based teacher algorithms could successfully guide DRL agents to learn and generalize in difficult continuously parameterized environments. With no prior knowledge of its student’s abilities and learning algorithm, and only loose boundaries on the environment space, ALP-GMM, our proposed teacher, consistently outperformed random heuristics and occasionally even expert-designed curricula. We show that it also scales when the procedural generation includes irrelevant dimensions or produces large proportions of unfeasible environments.

ALP-GMM, which is conceptually simple and has very few crucial hyperparameters, opens-up exciting perspectives inside and outside DRL for curriculum learning problems. Within DRL, it could be applied to previous work on autonomous goal exploration through incremental building of goal spaces. In this case several ALP-GMM instances could scaffold the learning agent in each of its autonomously discovered goal spaces. Another domain of applicability is personalization of sequences of exercises for human learners in educational technologies, or training humans for sensorimotor skills in re-habilitation or sports.

The full details of this work are presented in: Rémy Portelas, Cédric Colas, Katja Hofmann, Pierre-Yves Oudeyer (2019) Teacher algorithms for curriculum learning of Deep RL in continuously parameterized environments Proceedings of CoRL 2019 - Conference on Robot Learning , Oct 2019, Osaka, Japan. Bibtex.

Code

Jointly to this work, we release a github repository featuring implementations of ALP-GMM, RIAC and CovarGMM along with our parameterized BipedalWalker environments.

Contact

Email: remy.portelas@inria.fr

References

-

Togelius J., Champandard A.J., Lanzi, Pier Luca, Mateas M., Paiva A., Preuss Mike, Stanley K.O.. (2013). Procedural content generation: goals, challenges and actionable steps. Dagstuhl Follow-Ups. 6. 61-75. link

-

Open AI. (2019). Solving Rubik’s Cube with a Robot Hand. link

-

Blog post: Lilian Weng. (2019). Domain Randomization for Sim2Real Transfer. link

-

Cobbe K., Klimov O., Hesse C., Kim T., Schulman J.. (2019). Quantifying Generalization in Reinforcement Learning. link

-

Karl Cobbe, Christopher Hesse, Jacob Hilton, John Schulman.(2019). Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning. link

-

Laversanne-Finot A., Péré A., Oudeyer P-Y. (2018). Curiosity Driven Exploration of Learned Disentangled Goal Spaces. link

-

Lopes M., Oudeyer P-Y. (2012). The Strategic Student Approach for Life-Long Exploration and Learning. link

-

Oudeyer P.-Y., Gottlieb J., Lopes M. Intrinsic motivation, curiosity, and learning: Theory and applications in educational technologies. (2016). link

-

Oudeyer P.-Y., Kaplan F., Hafner V. (2007). Intrinsic Motivation Systems for Autonomous Mental Development. link

-

Forestier S., Oudeyer P.-Y.. (2016). Curiosity-Driven Development of Tool Use Precursors: a Computational Model. link

-

Forestier S., Mollard Y., Oudeyer P.-Y.. (2017). Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration Processes with Automatic Curriculum Learning link

-

Baranes A., Oudeyer P.-Y.. R-IAC: robust intrinsically motivated exploration and active learning. (2009). link

-

Moulin-Frier C., Nguyen S. M., Oudeyer P.-Y.. Self-organization of early vocal development in infants and machines: The role of intrinsic motivation. (2013). link

-

Auer P., Cesa-Bianchi N., Freund Y., Schapire R. E.. (2002). The Nonstochastic Multiarmed Bandit Problem. link

-

Bozdogan H.. (1987). Model selection and akaike’s information criterion (aic): The general theory and its analytical extensions. link

-

Ha. D. (2018). Reinforcement learning for improving agent design. link

-

Wang R. , Lehman J. , Clune J. , Stanley K. O.. (2019). POET: Endlessly Generating Increasingly Complex and Diverse Learning Environments and their Solutions through the Paired Open-Ended Trailblazer. link

-

Haarnoja T. , Zhou A., Abbeel P., Levine S.. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. (2018). link

-

Baranes A., Oudeyer P.-Y.. (2013). Active Learning of Inverse Models with Intrinsically Motivated Goal Exploration in Robots. link

-

Colas C., Sigaud O., Oudeyer P.-Y.. (2019). How Many Random Seeds? Statistical Power Analysis in Deep Reinforcement Learning Experiments. link

-

Clément B., Roy D., Oudeyer P.-Y., Lopes. M.. (2015). Multi-Armed Bandits for Intelligent Tutoring Systems. link